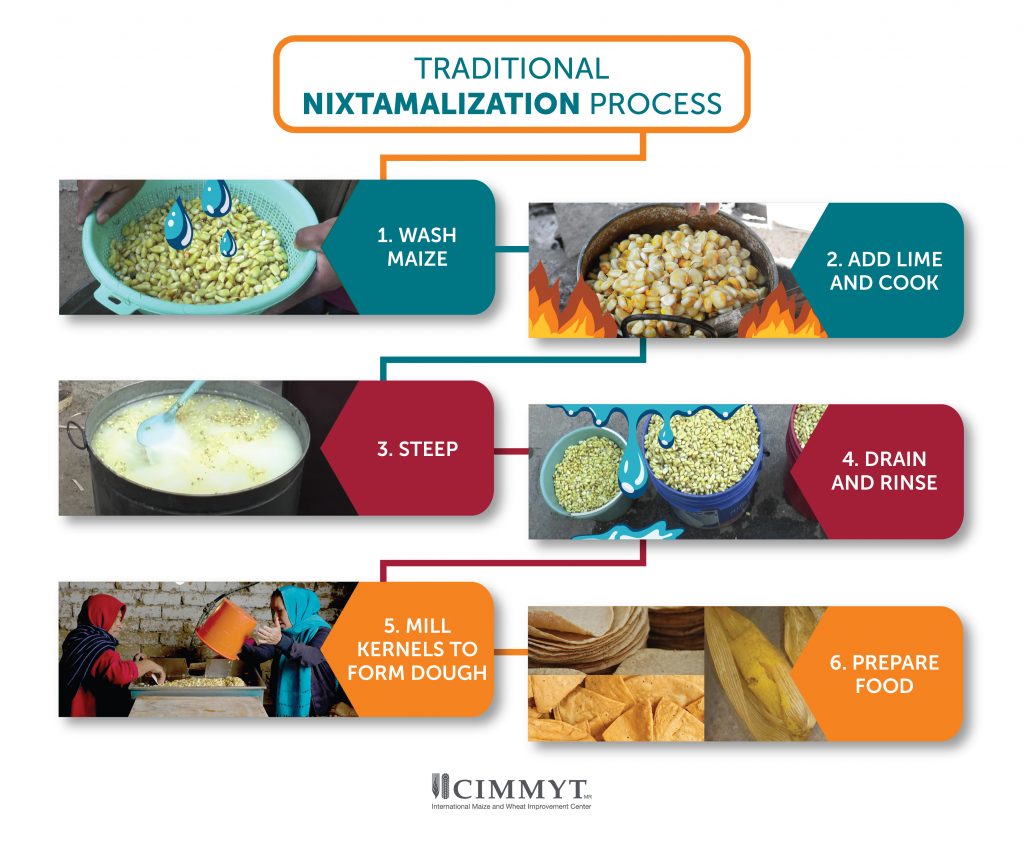

For centuries, people across Mexico and Central America have been using a traditional method, known as nixtamalization, to process their maize.

Now carried out both at household and industrial levels, this technique offers a range of nutritional and processing benefits. It could easily be adopted by farmers and consumers in other parts of the world.

What is nixtamalization?

Nixtamalization is a traditional maize preparation process in which dried kernels are cooked and steeped in an alkaline solution, usually water and food-grade lime (calcium hydroxide).

After that, the maize is drained and rinsed to remove the outer kernel cover (pericarp) and milled to produce dough that forms the base of numerous food products, including tortillas and tamales.

How does it work?

What happens when maize kernels are nixtamalized?

The cooking (heat treatment) and steeping in the alkaline solution induce changes in the kernel structure, chemical composition, functional properties and nutritional value.

For example, the removal of the pericarp leads to a reduction in soluble fiber, while the lime cooking process leads to an increase in calcium content. The process also leads to partial starch gelatinization, partial protein denaturation — in which proteins present in the kernel become insoluble — and a partial decrease in phytic acid.

What are the benefits of processing maize in this way?

In addition to altering the smell, flavor and color of maize products, nixtamalization provides several nutritional benefits including:

- Increased bioavailability of vitamin B3 niacin, which reduces the risk of pellagra disease

- Increased calcium intake, due to its absorption by the kernels during the steeping process

- Increased resistant starch content in food products, which serves as a source of dietary fiber

- Significantly reduced presence of mycotoxins such as fumonisins and aflatoxins

- Increased bioavailability of iron, which decreases the risk of anemia

These nutritional and health benefits are especially important in areas where maize is the dietary staple and the risk of aflatoxins is high, as removal of the pericarp is thought to help reduce aflatoxin contamination levels in maize kernels by up to 60% when a load is not highly contaminated.

Additionally, nixtamalization helps to control microbiological activity and thus increases the shelf life of processed maize food products, which generates income and market opportunities for agricultural communities in non-industrialized areas.

Where did the practice originate?

The word itself comes from the Aztec language Nahuatl, in which the word nextli means ashes and tamali means unformed maize dough.

Populations in Mexico and Central America have used this traditional maize processing method for centuries. Although heat treatments and soaking periods may vary between communities, the overall process remains largely unchanged.

Today nixtamalized flour is also produced industrially and it is estimated that more than 300 food products commonly consumed in Mexico alone are derived from nixtamalized maize.

Can farmers and consumers in other regions benefit from nixtamalization?

Nixtamalization can certainly be adapted and adopted by all consumers of maize, bringing nutritional benefits particularly to those living in areas with low dietary diversity.

Additionally, the partial removal of the pericarp can contribute to reduced intake of mycotoxins. Aflatoxin contamination is a problem in maize producing regions across the world, with countries as diverse as China, Guatemala and Kenya all suffering heavy maize production losses as a result. While training farmers in grain drying and storage techniques has a significant impact on reducing post-harvest losses, nixtamalization technology could also have the potential to prevent toxin contamination and significantly increase food safety when used appropriately.

If adapted, modern nixtamalization technology could also help increase the diversity of uses for maize in food products that combine other food sources like vegetables.

Cover photo: Guatemalan corn tortillas. (Photo: Marco Verch, CC BY 2.0 DE)

Nutrition, health and food security

Nutrition, health and food security