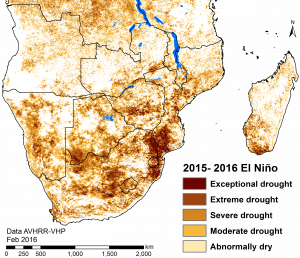

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) – El Niño may have passed, but food security in southern Africa will continue to deteriorate until next year, as farmers struggle to find the resources to rebuild their livelihoods. Currently, around 30 million people in southern Africa require food aid, expected to rise to 50 million people by the end of February 2017.

Two Zimbabwe-based scientists from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) highlighted predictions that El Niño will become more frequent and severe under climate change, and that heat stress will reduce maize yields in southern Africa by 2050. Research centers, development agencies and governments must work together to respond to climate predictions before food crises develop, they said.

Q: What do climate predictions say and how do they inform CIMMYT’s work?

Jill Cairns: Using climate projections we identified what future maize growing environments are going to be like, what traits will be needed for these environments and where the hotspots of vulnerability will be in terms of maize production.

We identified that heat stress is going to become a more important issue for maize in southern Zimbabwe, and southern Africa generally.

Previously we had no heat screening in the whole of Africa for maize breeding, and four years ago we set up heat screening networks. Through that we are starting to get maize varieties that do well under heat and drought.

This was meant to be for 2050, but now we have seen in this last El Niño that heat stress is a real problem. We actually have varieties now, thanks to the identification of the problem and the pre-emptive work towards it.

Q: What can be done for farmers in drought-stricken areas?

Christian Thierfelder: We have systems with adaptation qualities. For example, conservation agriculture increases water infiltration and maintains higher levels of soil moisture. So in times of dry spells, these systems can produce more, and live from the residual moisture in the soil.

Stress-tolerant maize is selected under drought and heat stress besides other biotic and abiotic stresses, and specifically adapted to such circumstances. We know that the varieties themselves can help farmers’ yields by 30 to 50 percent, but if you combine that with other technologies, and we have seen that this last year, you can have yield gains of over 100 percent with conservation agriculture and improved seed for example under drought conditions.

We have seen this year in Malawi, in communities that were heavily affected by El Niño, that we harvested almost two tons more maize per hectare in comparison to the conventional systems. I think this is a huge benefit that we really have to roll out.

Q: What can be achieved over the next five to seven years?

Christian Thierfelder: Our biggest aim is to improve and increase the resilience of farming systems. We are not looking at a single technology like drought tolerant maize or conservation agriculture in isolation, but looking at it more from livelihoods perspective and a farming systems perspective.

Besides technologies, we also need other climate-smart options and approaches that support farmers to respond to a changing climate. Farmers also need cash if they have failed in a drought year, and small loans or microfinancing will be critical to buy things from scratch and re-initiate farming.

We have the technologies, we have researched them and we know their impact on a small scale. What we want to do now is encourage public and private organizations, including seed companies, that work in that space to come together with us and jointly find solutions.

We as CIMMYT can only tackle a certain proportion of the farming system with our technologies and approaches. We have other CGIAR centers that specialize in legumes, cassava and livestock, and we partner a lot with international NGOs like Concern, Catholic Relief Services, CARE, World Vision, Total LandCare and the national agriculture research and extension systems to help us with scaling.

If we really come together now, if we have a coherent and joint multidisciplinary approach, I think in seven years’ time we will have reached many more farmers. We will target 10 million farmers practicing climate-smart agriculture in the next five to seven years.

Nutrition, health and food security

Nutrition, health and food security