A stakeholders consultation meeting co-organized by the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, The FAO Subregional Office for Southern Africa and CIMMYT on the Fall Armyworm in Africa will be held April 27 and 28, 2017 in Nairobi, Kenya. Delegates will discuss status and strategy for effective management.

NAIROBI, Kenya (CIMMYT) – Smallholder farmers in eastern and southern Africa are facing a new threat as a plague of intrepid fall armyworms creeps across the region, so far damaging an estimated 287,000 hectares of maize.

Since mid-2016, scientists with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and national agricultural research partners have been monitoring reports of sightings of the fall armyworm in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. Surveys conducted in farmers’ fields last year confirmed its presence in Kenya. The threat of the pest spreading into other eastern Africa countries is a significant risk due to similar planting seasons across the region.

To date, Zambia has confirmed reports that almost 90,000 hectares of maize have been affected, Malawi reports some 17,000 hectares have been hit, Zimbabwe reports a potential 130,000 hectares affected, while in Namibia, approximately 50,000 hectares of maize and millet have been damaged, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations.

FAO hosted an emergency meeting in Harare, Zimbabwe, last week to determine the best possible ways to manage the pest, which is native to the Americas and was first reported in Africa in January 2016.

In consultation and closely aligned with national partners in eastern and southern Africa, CIMMYT advises that Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is the best possible solution to effectively tackle the pest in both the short and long term.

A range of measures, including host plant resistance, chemical control, pheromone traps, biological control, habitat management, intercropping with legumes and diversification of farming systems can be effective. Fall armyworm infestations have been reduced by 20 to 30 percent on maize intercropped with beans compared to maize alone, research shows.

“Urgent collaborative efforts from CGIAR centers, national research partners and other research and development institutions in Africa must be deployed to design and develop an integrated pest management strategy, which can provide sustainable solutions to effectively tackle the adverse effects of the fall armyworm,” said Martin Kropff, CIMMYT’s director general. “The strategy should also include early warning systems that track the movements of the pest.”

“Scientists at CIMMYT are currently researching available breeding resources characterized with potential resistance to fall armyworm and screening elite maize germplasm to identify possible sources of resistance,” said B.M. Prasanna, director of CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program and the CGIAR Research Program MAIZE. “Maize lines with partial resistance to fall armyworm were developed in the past, but the work was not scaled-up given the need to focus breeding programs on other high priority traits, including drought tolerance, heat tolerance, and resistance to major diseases, such as maize lethal necrosis (MLN).”

“Breeding for fall armyworm resistant elite maize hybrids adapted to sub-Saharan Africa would require intensive germplasm screening and collaborative work with public and private sector partners,” Prasanna added, explaining that CIMMYT can mobilize its vast germplasm resources as well as modern breeding tools to speed up the breeding process, in a similar manner to the efforts being undertaken to tackle the menace of MLN in eastern Africa.

Why is the Fall Armyworm so destructive?

The fall armyworm – Spodoptera frugiperda – was first reported on the African continent in Nigeria. It subsequently appeared across parts of West and Central Africa, before extensively invading farmers’ fields in southern Africa in December 2016. The destructive activities of the fall armyworm have only served to add to devastation caused by the native African armyworm (Spodoptera exempta) and severe drought caused by an El Nino weather system in 2015-2016.

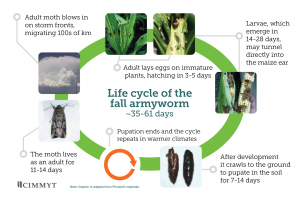

The larvae of the pest proliferate mainly due to wind dispersal and on host plants from eggs laid by moths. The pest can cause crop losses of up to 73 percent and once it is at an advanced larval development stage can become difficult to control with pesticides.

In the United States, the fall armyworm ranks second among seven of the most damaging agricultural pests leading to significant economic losses both on crops and wild plant species. A study estimates that total losses in the United States range from $39 million to $297 million annually and that related annual maize yield loss is 2 percent.

How the pest was introduced in Africa from its native habitat in the Americas is unclear. However, such invasive pests as the fall armyworm are known to cross continents either through infested commercial grain or through jet streams across oceans. Many fall armyworm moths have been collected in the Gulf of Mexico as far as 250 km from land, indicating the possibility of seasonal trans-Gulf migration between the United States and the tropics.

“We need to understand better the behavioral ecology of the fall armyworm in the Africa context. How it breeds, travels and feeds on crops, as this is critical for effectively managing the devastation this pest can cause and its major risk to food security,” Martin Kropff cautioned.

It is particularly hard to control, as the moths are strong flyers, breed at an exponential rate, and the larvae can feed on a wide variety of plant species. In addition, it can quickly develop resistance to pesticides if they are not used judiciously. The larvae burrow into the growing point of the maize plants and destroy the growth potential of plants or clip the leaves. They also burrow into the ear and feed on kernels.

CIMMYT scientists respond to some Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) regarding fall armyworm:

Q: Is the presence of fall armyworm confirmed in Kenya?

A: Yes. A survey carried out from June to August 2016 in Embu and Kisii counties showed fall armyworm infestation. Although the infestation is still low in comparison to other parts of the region, the situation could change. Scientists from the University of Nairobi also reported sightings of fall armyworm maize damage in Machakos County. Anani Bruce, CIMMYT Maize Entomologist, Nairobi, Kenya

Q: Does CIMMYT have fall armyworm-resistant maize varieties?

A: We do have a few CIMMYT maize inbred lines that can potentially offer partial resistance to the fall armyworm, but intensive breeding efforts are needed to identify more sources of resistance and to develop Africa-adapted improved maize hybrids with resistance to fall armyworm, including other relevant traits required by smallholders in the continent. B.M Prasanna, director of CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program & CGIAR Research Program MAIZE.

Q: There are reports of transgenic maize with resistance to fall armyworm; has this been confirmed?

A: A transgenic maize trial (under Confined Field Trials) was attacked by the fall armyworm in Namulonge and Kassesse (Uganda) during the first and second cropping seasons in 2016. The MON810 Bt maize entries showed resistance to the fall armyworm compared to non-transgenic maize materials. This however, needs to be further confirmed through additional experiments. Anani Bruce, CIMMYT Maize Entomologist

(Editing by Julie Mollins)

Nutrition, health and food security

Nutrition, health and food security