March, 2005

The greatest pest of crops

The greatest pest of crops-Roman philosopher Pliny, AD 100

Nearly 2000 years after Pliny’s description of stem rusts, plant disease scientist William Wagoire made a startling observation in a Ugandan wheat field. The telltale reddish brown spores he saw on the wheat plants were unmistakable and most unwelcome—they heralded a resurgence of stem rust.

The interim between Pliny and Wagoire’s sightings saw the scourge, which is capable of destroying 100% of a crop, emerge and dissipate countless times at various locations worldwide. Ancient Greeks struggled with it, the Romans sacrificed red animals such as foxes and dogs every spring to appease their rust god Robigus, and the US epidemics of 1916 and 1957 ravaged the nation’s wheat belt. A reprieve came in the 1960s with Norman Borlaug’s semi-dwarf wheat lines, which carried resistance to rust and wiped the worry from farmers’ and scientists’ minds. But now a new strain, called UG99, has reared its head—it is destroying harvests in East Africa and moving fast.

Wheat’s nemesis, rust is a fungus that spreads quickly over large areas. Tiny spores readily take to the wind and can travel thousands of kilometers via the atmospheric jet streams. With the proliferation of intensive agricultural systems since the 1970s, the stem rust fungus has greater opportunity to multiply, mutate, and evolve, and this is what we may now be witnessing. Since Wagoire’s discovery in Uganda, it was found in Kenya in 2000, Ethiopia in 2002, and there is no reason to believe it will halt its march.

“Stem rust has been a severe disease in the Indian Subcontinent, and it is only a matter of time until the new strain reaches across the Saudi Arabian peninsula and into the Middle East, South Asia, and eventually East Asia,” says Ravi Singh, CIMMYT wheat pathologist. It could also reach Australia and the Americas in the clothes of people who travel in and out of East Africa.

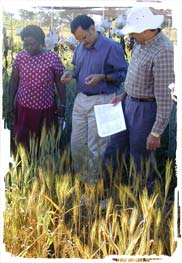

For those Eastern African farmers who can afford it, fungicides offer a short-term defense. When the disease is in epidemic form, however, greater and greater amounts of chemicals are needed to achieve control. Also, this method exerts a considerable toll on the environment. Breeding for new genetic resistance is the preferred technique, especially given the estimates that half of the world’s bread wheat is susceptible.

“The situation is ready for an explosive disaster,” warns Borlaug, who is leading a campaign for concerted action against the new strain.

Funding is currently being sought for a CIMMYT-led Global Rust Initiative (GRI), promoted by Borlaug and others, which will allow breeders to better monitor the spread of the disease and to develop resistant wheat varieties. There is also a vital need to revive training for rust research, and to support such work at the national level.

For further information, contact Dr. Ravi Singh (r.singh@cgiar.org).

Capacity development

Capacity development