Eleven years ago this week, Apple Inc. released the iPhone. While it was not the first smartphone on the market, industry experts often credit the iPhone’s groundbreaking design with the launch of the mobile revolution. The device, its competitors and the apps that emerged with them have changed how over two billion people interact with the world on a daily basis.

Eleven years ago this week, Apple Inc. released the iPhone. While it was not the first smartphone on the market, industry experts often credit the iPhone’s groundbreaking design with the launch of the mobile revolution. The device, its competitors and the apps that emerged with them have changed how over two billion people interact with the world on a daily basis.

The success of this revolution, however, goes far beyond the actual technology. At the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) outside Mexico City, scaling expert Lennart Woltering points to a smartphone lying on his desk.

“We have to remember that this phone is just hardware. It is useless if you don’t have a network connection or an outlet in your house with electricity,” he says.

Woltering joined CIMMYT last year as part of the German Development Cooperation’s effort to aid the scaling-up of agricultural innovations. New, improved seeds, small-scale machinery and conservation practices can all play a role in achieving several of the Sustainable Development Goals, but Woltering says many other non-technological factors, such as markets and policies, can prevent these innovations from having significant impact.

“Many research institutes and nongovernmental organizations tend to focus on technology as the solution for everything,” he says. “But we find that 9 out of 10 cases, limiting factors have more to do with financing not being available to people, or poor policies that are hampering the adoption of technology.”

For example, CIMMYT has many initiatives in South Asia to promote conservation agriculture. Adopting no-till practices can help reduce erosion and improve soil health for better yields, but farmers who make this transition often need access to a different kind of machinery, such as the Happy Seeder, to plant their seeds. If government subsidies exist for conventional rototillers but not for the Happy Seeder, it is difficult to persuade farmers to make that economic sacrifice.

“It is a completely different ballgame in the real world, and you have to be honest about whatever fake reality you created in your project,” says Woltering.

Projects are designed in a very controlled way. They have a fixed budget and a fixed end date, and they are often shielded from the social and economic complexities that can propel or hinder an innovation from scaling.

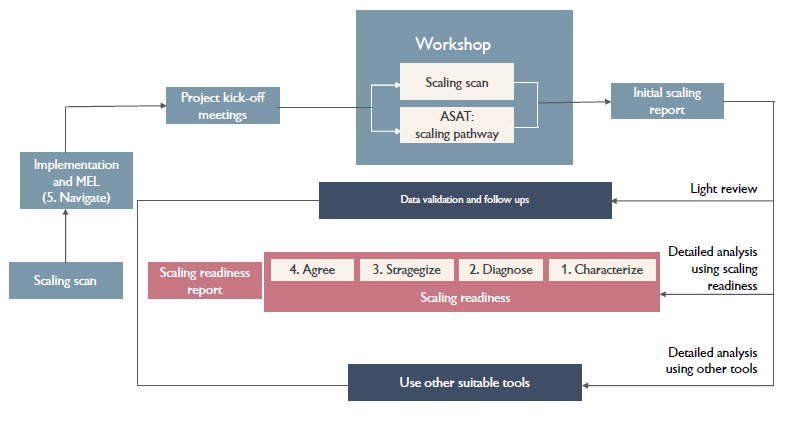

“So if a donor says, ‘We want two million people to be reached,’ well, how are you going to do that? That’s where the Scaling Scan can help,” says Woltering.

The Scaling Scan helps an individual analyze, reflect on, and sharpen one’s scaling ambition and approach through a series of questions and prompts. It focuses on ten scaling ‘ingredients’ that need to be considered (e.g. knowledge and skills, public sector governance, awareness and demand) to reach the desired outcome.

“The Scaling Scan helps you figure out what exactly is required, what is possible, and what bottlenecks exist that you need to address in your strategy,” Woltering says.

Woltering collaborated with The PPPLab, a consortium of four Dutch institutes, to release the first version of the Scaling Scan last year. They tested it with project teams in the Netherlands, Mexico, India, Nepal and Kenya, and based on the feedback, they are now releasing a second version, which is available here.

In the trials with the first Scaling Scan, some teams realized the results they wanted to achieve were too ambitious given the circumstances. For other teams, it helped them clarify exactly what they wanted to achieve.

“Having a project objective is not enough to internalize the main goal,” says Woltering. “It also changes over time, especially if it’s a long-term project. The scaling scan can be good for an annual checkup.”

Woltering emphasizes that successful scaling requires multidisciplinary collaboration.

“If you only have a team of agronomists, you will not reach a scale of millions you want to achieve. If you only have a team of policy experts, you will not succeed,” he says. “There are professionals that can really help and add value to what we are doing.”

“It’s hard to get an agronomist and an economist in the same room together, but we’re not going to change the world if we don’t work together with others who have their specific specialty or expertise,” he says.

The Scaling Scan also includes a responsibility check through some very simple but strategic questions.

“Every system has its pros and cons – some people benefit, some do not. Some have power, some do not,” says Woltering. “So what does it mean if your innovation goes to scale? Maybe there’s a whole new power dimension.”

Successfully scaling something may have unintended consequences. There are always tradeoffs and resistance to change. Woltering says the responsibility check can help actors in the development sector to think through these questions and consider what the possible outcomes could be.

For more explanation on how and when to use the tool, we invite you to download the Scaling Scan (also available in Spanish) which contains detailed practical information. We recommend the Excel sheet (also available in Spanish) to have the average scores and results generated automatically. A condensed, two-page PDF is also available.

This work is supported by the German Development Cooperation (GIZ) and led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

Gender equality, youth and social inclusion

Gender equality, youth and social inclusion