Responsible for 80% of the food we eat and 98% of the oxygen we breathe, plants are a pillar of life on earth. But they are under threat. Up to 40 percent of food crops are lost to plant pests and diseases each year according to the FAO.

When disease outbreaks occur, the impacts can be devastating. In the 1840s, the Irish potato famine, caused by the fungal disease late blight, killed around one million people and caused another million to emigrate.

The recent invasion of desert locusts throughout the horn of Africa – the worst in decades – shows how vulnerable crops are to pests as well.

The desert locust is one of the most destructive pests in the world, with one small swarm covering one square kilometer eating the same amount of food per day as 35,000 people. The outbreak could even provoke a humanitarian crisis, according to the FAO.

How does climate change affect pests and diseases?

Climate change is one factor driving the spread of pests and diseases, along with increasing global trade. Climate change can affect the population size, survival rate and geographical distribution of pests; and the intensity, development and geographical distribution of diseases.

Temperature and rainfall are the big drivers of shifts in how and where pests and diseases spread, according to experts.

“In general, an increase in temperature and precipitation levels favors the growth and distribution of most pest species by providing a warm and humid environment and providing necessary moisture for their growth,” says Tek Sapkota, agricultural systems and climate change scientist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

However, when temperatures and precipitation levels get too high, this can slow the growth and reproduction of some pest species and destroy them by washing their eggs and larvae off the host plant, he explains.

This would explain why many pests are moving away from the tropics towards more temperate areas. Pests like warmer temperatures – but up to a point. If it is too hot or too cold, populations grow more slowly. Since temperate regions are not currently at the optimal temperature for pests, populations are expected to grow more quickly in these areas as they warm up.

Crop diseases are following a similar pattern, particularly when it comes to pathogens like fungi.

Movement towards the earth’s poles

Research shows that since 1960, crop pests and diseases have been moving at an average of 3 km a year in the direction of the earth’s north and south poles as temperatures increase.

Tar spot, a fungal disease native to Latin America, which can cause up to 50% of yield losses in maize, was detected for the first time in the US in 2015. Normally prevalent in tropical climates, the disease has started emerging in non-tropical regions, including highland areas of Central Mexico and many counties in the US.

The southern pine beetle, one of the most destructive insects invading North America, is moving north as temperatures rise and is likely to spread throughout northeastern United States and into southeastern Canada by 2050.

Wheat rusts, which are among the greatest threats to wheat production around the world, are also adapting to warmer climates and becoming more aggressive in nature, says Mandeep Randhawa, CIMMYT wheat breeder and wheat rust pathologist.

“As temperatures rise, larger quantities of spores are produced that can cause further infection and could potentially result in pathogenic changes through faster rate of their evolution.”

Scientists recently reported that stem rust had emerged in the UK for the first time in 60 years. Climate changes over the past 25 years are likely to have encouraged conditions for infection, according to the study.

Rising CO2 levels

Rising carbon dioxide (CO2) levels could also affect pests indirectly, by changing the architecture of their host plant and weakening its defenses.

“Elevated CO2 concentrations, as a result of human activity and influence on climate change, will most likely influence pests indirectly through the modification in plant chemistry, physiology and nutritional content,” says Leonardo Crespo, CIMMYT wheat breeder.

Rising CO2 concentrations and temperatures could also provide a more favorable environment for pathogens like fungi, reports the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Despite high confidence among scientists that climate change will cause an increase in pests and diseases, predicting exactly when and where pests and diseases will spread is no easy task. There is significant variation between different species of pests and types of pathogens, and climate models can only provide estimates of where infection or outbreaks might occur.

Keeping pests and disease pandemics at bay

To address these uncertainties, experts increasingly recognize the need to monitor pest and disease outbreaks and have called for a global surveillance system to monitor these and improve responses.

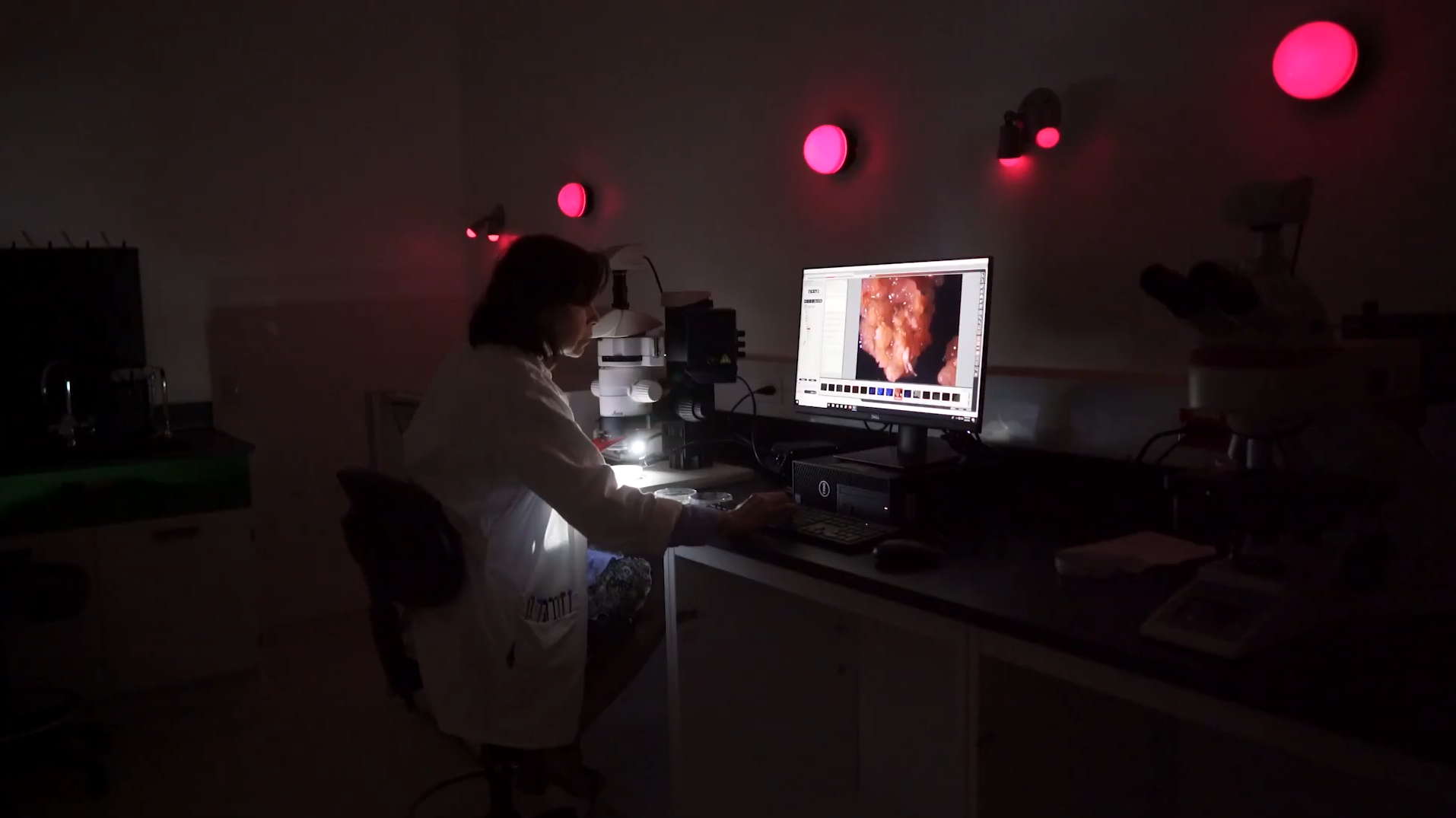

Recent technological tools like the suitcase-sized mobile lab MARPLE, which tests pathogens such as wheat rust in near real-time and gives results within 48 hours, allow for early detection. Early warning systems are also crucial tools to warn farmers, researchers and policy makers of potential outbreaks.

Breeding pest- and disease-resistant varieties is another environmentally friendly solution, since it reduces the need for pesticides and fungicides. Collaborating with scientists worldwide, CIMMYT works on developing wheat and maize varieties resistant to diseases, including Fusarium Head Blight (FHB), wheat rust, wheat blast for wheat and maize lethal necrosis (MLN) for maize.

Beneficial insects can also act as a natural pest control for crops. Ladybugs, spiders and dragonflies act as natural predators for pests like aphids, caterpillars and stem borers. Other solutions include mechanical control measures such as light traps, pheromone traps and sticky traps, as well as farming practice controls such as crop rotation.

The United Nations has declared this year as the International Year of Plant Health, emphasizing the importance of raising global awareness on how “protecting plant health can help end hunger, reduce poverty, protect biodiversity and the environment, and boost economic development.”

As part of this initiative, CIMMYT will host the 24th Biannual International Plant Resistance to Insects (IPRI) conference from March 2-4. The conference will cover topics including plant-insect interactions, breeding for resistance, and phenotyping technologies for predicting pest resistant traits in plants.

Cover photo: A locust swarm in north-east Kenya. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization has warned that the swarms already seen in Somalia, Kenya and Ethiopia could range further afield. Photograph: Sven Torfinn/FAO

Capacity development

Capacity development