March, 2005

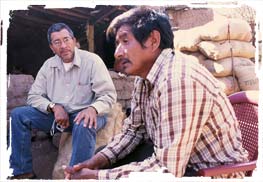

Farmer Juan Castillejos Castro of the village Dolores, Jaltenango, state of Chiapas, in southeastern Mexico, leaned forward in the humid, mid-morning heat and pondered the question: had household nutrition improved in the last 10 years? “From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, even I was malnourished to the point I couldn’t work,” he says. “Now things have gotten better, and the credits have helped a lot.”

Farmer Juan Castillejos Castro of the village Dolores, Jaltenango, state of Chiapas, in southeastern Mexico, leaned forward in the humid, mid-morning heat and pondered the question: had household nutrition improved in the last 10 years? “From the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, even I was malnourished to the point I couldn’t work,” he says. “Now things have gotten better, and the credits have helped a lot.”

Like many farmers in the “La Frailesca” region of Chiapas, Castillejos has been growing improved, hybrid maize, through a state-sponsored program that offers seed plus other inputs (fertilizer, pesticides, among them) and services (technical advice, crop loss insurance, to name two) on credit, to be repaid at harvest. For the last decade, government policy has also discouraged the burning of crop residues. Burning helped farmers control weeds and pests, but bared often steep, hillside plots to eroding winds and rain and deprived soils of organic matter. Castillejos and most peers now practice a more resource-conserving style of agriculture, sowing with a stick directly into the last year’s crop residues, without plowing or burning.

Folk Varieties Fading in La Frailesca

Unlike many farmers adopting the hybrids, Castillejos still grows small plots of the local maize varieties developed through selection by millennia of predecessors. The local varieties feature a better grain type for tortillas and other preferred foods. Their weaknesses include tallness and a tendency to topple easily. This and their relatively low yields have put them on the road to extinction, according to Dagoberto Flores, research assistant in CIMMYT’s Impacts Assessment and Targeting Program.

“We still need a systematic study on this,” says Flores, “but I would guess that half the local varieties have disappeared, and only 30% of farmers are growing any local materials.” Flores and an associate, Alejandro Ramírez López, just spent a month surveying 120 farm households in 4 communities in the region. With funding from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), they are comparing the costs to farmers of obtaining seed through formal versus informal supply systems and evaluating farmers’ risks, from village to village.

The village of Dolores Jaltenango lies in the mountainous countryside that bred the Zapatista uprising and is a gateway for undocumented immigrants from Central America. Nine-tenths of maize is relegated to steep hillsides—cattle raising and plantation agriculture claim the choice lowlands. “Dolores is one of the poorer communities in the area,” says Flores. “Dwellings are adobe with dirt floors. There’s normally one large sleeping quarters for an average 10 people, including parents, children, and married children’s spouses.”

Flores and Ramírez are concerned about La Frailesca’s farmers. The prices of the seed technology packages are rising steadily, and subsidies are being reduced. They fear that if farmers lose their native seed, they may have no fallback position. “Farmers look at their neighbor’s yields or the size of the ears, but most haven’t done the math on all the costs and benefits of the new technology,” Ramírez says. He cites the results of last year’s serious drought as an example: “Many farmers had poor crops. But some didn’t qualify for crop loss insurance benefits. Now they’re having trouble paying back their credit debts.”

CIMMYT’s Role: Conserving and Replenishing Diversity

According to Flores, CIMMYT staff have collected and preserved important samples of the Frailesca’s farmer varieties in the center’s germplasm bank. The bank contains seed collections for an estimated 80% of all Latin American maize diversity, including many varieties no longer sown by farmers. The seed is kept in trust for humanity, under a 1994 agreement with FAO. Working with partners in 13 countries in the Americas, center staff have coordinated the rescue, regeneration, and back-up storage of more than 10,000 seed samples of unique maize varieties from this hemisphere. CIMMYT and partners from the Mexican National Institute of Agriculture, Forestry, and Livestock Research (INIFAP) recently restored seed of local varieties to farmers in Oaxaca, Mexico, and could do the same for Chiapas farmers, should this become necessary, Flores says.

Fitting into FAO Research Efforts

Environmental economist Leslie Lipper at FAO will draw on the survey and its results in an emerging, multi-country study on how market access to crop genetic resources affects farmers’ welfare and on-farm crop biological diversity, according to Kostas Stamoulis, Chief of the FAO Agricultural Sector in Economic Development Service (ESAE). “CIMMYT’s work will provide unique data on farmer seed sourcing choices,” says Stamoulis. “Among other things, we’ll get a better read on how those choices are affected by the transaction costs of market participation and farmer’s perceptions of risk.” The study is one of three major ESAE efforts to understand the role of markets in rural livelihoods and environmental sustainability.

Nutrition, health and food security

Nutrition, health and food security