Grafting is the technique of joining the shoot of one plant with the root of another, so they continue to grow together as one. Until now it was thought impossible to graft grass-like plants in the group known as monocotyledons because they lack a specific tissue type, called the vascular cambium, in their stem.

Researchers at the University of Cambridge have discovered that root and shoot tissues taken from the seeds of monocotyledonous grasses — representing their earliest embryonic stages — fuse efficiently. Their results are published today in the journal Nature.

An estimated 60,000 plants are monocotyledons; many are crops that are cultivated at enormous scale, for example rice, wheat and barley.

The finding has implications for the control of serious soil-borne pathogens including Panama Disease, or Tropical Race 4, which has been destroying banana plantations for over 30 years. A recent acceleration in the spread of this disease has prompted fears of global banana shortages.

“We’ve achieved something that everyone said was impossible. Grafting embryonic tissue holds real potential across a range of grass-like species. We found that even distantly related species, separated by deep evolutionary time, are graft compatible,” said Julian Hibberd in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Plant Sciences, senior author of the report.

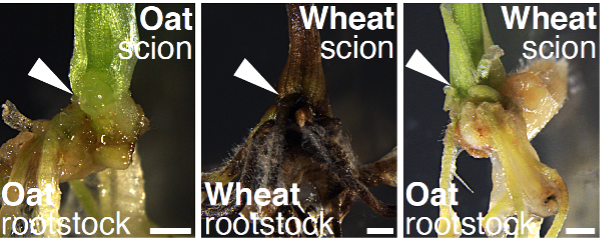

The technique allows monocotyledons of the same species, and of two different species, to be grafted effectively. Grafting genetically different root and shoot tissues can result in a plant with new traits — ranging from dwarf shoots, to pest and disease resistance.

Alison Bentley, CIMMYT Global Wheat Program Director and a contributor to the report, sees great potential for the grafting method to be applied to monocot crops grown by resource-poor farmers in the Global South. “From our major cereals, wheat and rice, to bananas and matoke, this technology could change the way we think about adapting food security crops to increasing disease pressures and changing climates.”

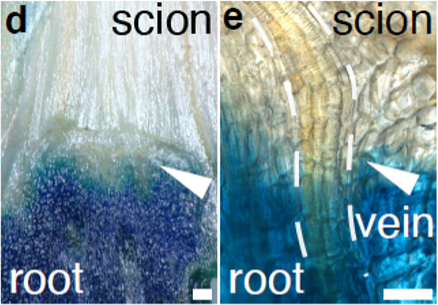

High magnification images show successful grafting of wheat in which a connective vein forms between root and shoot tissue after four months. White arrows show the graft junction. (Photo: Julian Hibberd)Monocotyledons breakthrough

The scientists found that the technique was effective in a range of monocotyledonous crop plants including pineapple, banana, onion, tequila agave and date palm. This was confirmed through various tests, including the injection of fluorescent dye into the plant roots — from where it was seen to move up the plant and across the graft junction.

“I read back over decades of research papers on grafting and everybody said that it couldn’t be done in monocots. I was stubborn enough to keep going — for years — until I proved them wrong,” said Greg Reeves, a Gates Cambridge Scholar in the University of Cambridge Department of Plant Sciences, and first author of the paper.

“It’s an urgent challenge to make important food crops resistant to the diseases that are destroying them,” Reeves explained. “Our technique allows us to add disease resistance, or other beneficial properties like salt-tolerance, to grass-like plants without resorting to genetic modification or lengthy breeding programmes.”

The world’s banana industry is based on a single variety, called the Cavendish banana — a clone that can withstand long-distance transportation. With no genetic diversity between plants, the crop has little disease-resilience. And Cavendish bananas are sterile, so disease resistance cannot be bred into future generations of the plant. Research groups around the world are trying to find a way to stop Panama Disease before it becomes even more widespread.

Grafting has been used widely since antiquity in another plant group called the dicotyledons. Dicotyledonous orchard crops — including apples and cherries, and high-value annual crops including tomatoes and cucumbers — are routinely produced on grafted plants because the process confers beneficial properties, such as disease resistance or earlier flowering.

The researchers have filed a patent for their grafting technique through Cambridge Enterprise. They have also received funding from Ceres Agri-Tech, a knowledge exchange partnership between five leading universities in the United Kingdom and three renowned agricultural research institutes.

“Panama disease is a huge problem threatening bananas across the world. It’s fantastic that the University of Cambridge has the opportunity to play a role in saving such an important food crop,” said Louise Sutherland, Director of Ceres Agri-Tech.

Ceres Agri-Tech, led by the University of Cambridge, was created and managed by Cambridge Enterprise. It has provided translational funding as well as commercialisation expertise and support to the project, to scale up the technique and improve its efficiency.

This research was funded by the Gates Cambridge Scholarship programme.

Read the study:

Monocotyledonous plants graft at the embryonic root-shoot interface

FOR MORE INFORMATION, OR TO ARRANGE INTERVIEWS, CONTACT THE MEDIA TEAM:

Marcia MacNeil, Head of Communications, CIMMYT.

Jacqueline Garget, Communications Manager, Office of External Affairs and Communications, University of Cambridge

ABOUT THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE:

The University of Cambridge is one of the world’s top ten leading universities, with a rich history of radical thinking dating back to 1209. Its mission is to contribute to society through the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence.

The University comprises 31 autonomous Colleges and 150 departments, faculties and institutions. Its 24,450 student body includes more than 9,000 international students from 147 countries. In 2020, 70.6% of its new undergraduate students were from state schools and 21.6% from economically disadvantaged areas.

Cambridge research spans almost every discipline, from science, technology, engineering and medicine through to the arts, humanities and social sciences, with multi-disciplinary teams working to address major global challenges. Its researchers provide academic leadership, develop strategic partnerships and collaborate with colleagues worldwide.

The University sits at the heart of the ‘Cambridge cluster’, in which more than 5,300 knowledge-intensive firms employ more than 67,000 people and generate £18 billion in turnover. Cambridge has the highest number of patent applications per 100,000 residents in the UK.

ABOUT CIMMYT:

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) is the global leader in publicly-funded maize and wheat research and related farming systems. Headquartered near Mexico City, CIMMYT works with hundreds of partners throughout the developing world to sustainably increase the productivity of maize and wheat cropping systems, thus improving global food security and reducing poverty. CIMMYT is a member of the CGIAR System and leads the CGIAR Research Programs on Maize and Wheat and the Excellence in Breeding Platform. The Center receives support from national governments, foundations, development banks and other public and private agencies.

Cover photo: A banana producer in Kenya. (Photo: N. Palmer/CIAT)

Climate adaptation and mitigation

Climate adaptation and mitigation