In our hyper-connected world, it should come as no surprise that recent years have shown a major uptick in the spread of transboundary pests and diseases. Integrated approaches have been effective in sustainably managing these border-jumping threats to farmers’ livelihoods and food security.

But a truly integrated approach accounts for not just the “cure,” but also how it can be sustainably incorporated into the agri-food system and social landscape. For example, how do we know if the farmers who adopt disease- and pest-resistant seed will be able to derive better incomes? And how do we ensure that incentives are aligning with community norms and values to enable better adoption of integrated disease or pest management approaches?

Experts from across the CGIAR research system and its partners weighed in on this topic in the recent webinar on Integrated Pest and Disease Management, the third in the International Year of Plant Health Webinar series. Panelists shared valuable perspectives on the science of outbreaks, the social dimensions of crop pest and disease control, zoonotic disease risk, and how national, regional and global organizations can better coordinate their responses.

“The combination of science, global partnerships and knowledge helps all of us be better prepared to avoid the losses we’ve seen. . . Today, we’re going to see what this looks like in practice,” said Rob Bertram, chief scientist for the Bureau for Resilience and Food Security at USAID, and moderator of the event.

Understanding the sources

Wheat and maize, the key crops studied at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) are no stranger to destructive diseases or pests, with fall armyworm, wheat blast, or maize lethal necrosis topping the list. But other staple crops and their respective economies are suffering as well — from infestations of cassava brown streak, potato cyst nematode, taro blight, desert locusts, and fusarium wilt, just to name a few.

What are the reasons for the expansion of these outbreaks? B.M. Prasanna, director of CIMMYT’s Global Maize Program explained that there are several: “Infected seed or planting material, vector movement, strong migratory capacity, contaminated field equipment, improper crop production commercialization practices, and global air and sea traffic” are all major causes.

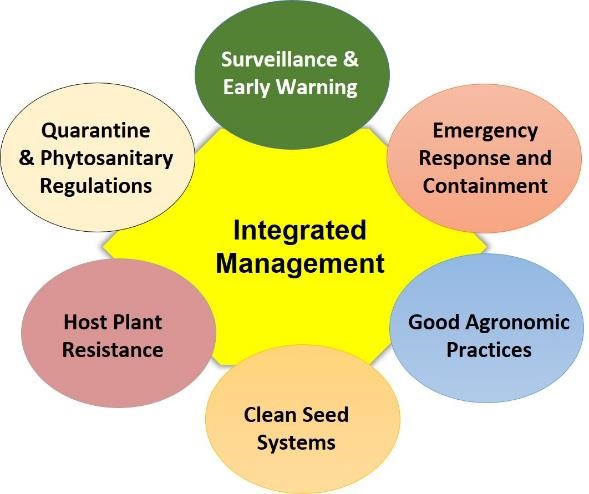

Preventing outbreaks is always better than scrambling to find a cure, but as Prasanna pointed out, this requires a holistic, multi-institutional strategy including surveillance and early warning, quarantine and phytosanitary regulations, and technological solutions. Better access to monitoring and surveillance data, and sensitive, easy-to-use and affordable diagnostic equipment are essential, as is the proactive deployment of resistant crop varieties.

Building awareness about integrated disease and pest management is just as important, he told the attendees. “We must remember that IPM is not just Integrated Pest Management, but also ‘Integrating People’s Mindsets.’ That remains a major challenge. We need to think beyond our narrow disciplines and institutions and really come together to put IPM solutions into farmers’ fields,” Prasanna said.

Not all outbreaks are the same, but lessons can be shared

Regina Eddy, coordinator for the Fall Armyworm Interagency Task Force at USAID, works closely with the complex issue of scaling when it comes to disaster response and the roles of national, regional and global organizations.

“We need to develop inclusive partner stakeholder platforms, not designed ‘for them,’ but ‘with them,’” said Eddy. “We cannot tackle food security issues alone. Full stop.”

Closing the gap between social and biophysical science

Nozomi Kawarazuka, social anthropologist at the International Potato Center (CIP) explained how researchers can improve the uptake of their new seed, innovation, or agronomic practice by involving social scientists to understand the gender norms and social landscape at the beginning of the project — in the initial assessment phase.

Kawarazuka highlighted how involving women experts and extension workers in sectors that are typically male-dominated helps reduce bias and works towards changing perceptions.

“In South Asia, women farmers hesitate to engage with male government extension workers,” she said. “Women experts and extension workers reduce this barrier. Gender and social diversity in the plant health sector is an entry point to develop innovations that are acceptable to women as well as men and helps scale up adoption of innovations in the community.

The world is watching agriculture and livestock

Zoonotic diseases, or zoonoses, are caused by pathogens spread between animals and people. Understanding zoonotic disease risk is an essential and timely topic in the discussion of integrated pest management. Poor livestock management practices, lack of general knowledge on diseases and unsafe yet common food handling practices put populations at risk.

“It’s especially timely, [to have this] zoonosis discussion in our COVID-plagued planet. The whole world is going to be looking to the food and agricultural sectors to do better,” Bertram said.

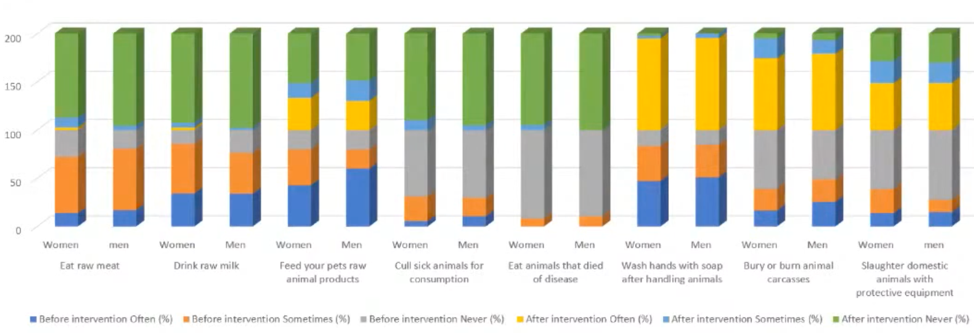

Annet Mulema, a gender and social scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) described results of a study showing how community conversations transformed gender relations and zoonotic disease risk in rural Ethiopia, where 80% of the population depends on agriculture and has direct contact with livestock.

“There were noticeable changes in attitude and practices among men and women regarding unsafe handling of animals and consumption of animal-source foods,” Mulema explained. “Community conversations give men and women involved a voice, it allows for a variety of ideas to be expressed and discussed, leads to community ownership of conclusions and action plans, and opens communication channels among local service providers and community members.”

Local to global, and global to local

Panelists agreed that improving capacity is the most powerful lever to advance approaches for integrated pest management and plant health, while connected and inclusive partnerships along the value chain make the whole system more resilient. The amount of scientific knowledge on ways to combat plant pests and diseases is increasing, and we have new tools to connect the global with the local and bring this knowledge to the community level.

The fourth and final CGIAR webinar on plant health is scheduled for March 31 and will focus on a the intersectional health of people, animals, plants and their environments in a “One Health” approach.

Gender equality, youth and social inclusion

Gender equality, youth and social inclusion