NAIROBI (CIMMYT) – Climate change’s impact in eastern and southern Africa has driven many farmers to seek new planting techniques that maintain or increase crop production, despite fewer resources.

The World Bank forecasts show that climate change will push Africa to surpass Asia as the most food insecure region in the world, inhabiting up to 50 percent of undernourished people globally in 2080. Variations in temperature and precipitation, coupled with prolonged droughts and floods during El Nino events is predicted to have a devastating impact in the region where 95 percent of all agriculture is dependent on rainfall.

Farmers in eastern and southern Africa are already feeling the impacts of climate change, and changing the way they make a living because of it through new agricultural adaptation strategies.

Sustainable practices like growing two or more crops among each other, or intercropping, have become popular with smallholder farmers in Africa who often plant multiple crops. When used in combination with improved seeds with traits like drought or disease resistance, these farmers are able to have successful harvests despite challenges imposed by climate change.

Knowing how to manage an intercropping system is vital to its success. Cereals and legumes in an intercrop system must have different growth habits and rooting patterns to reduce competition for nutrients, light and water.

According to Leonard Rusinamhodzi, an agronomist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), farmers also need to reduce herbicide use in intercropping systems.

“It’s difficult to apply selective herbicides in systems with both narrow and broad leaf crops,” said Rusinamhodzi, who is working with farmers to apply the best fertilizer practices to their intercropped plots. “Maize will require mostly nitrogen, phosphate and potassium basal fertilizer, while legumes will require mostly phosphate and potassium, and micronutrients such as zinc and boron. Proper rates and proportions for all fertilizers and nutrients is crucial to ensure both crops are properly nourished.”

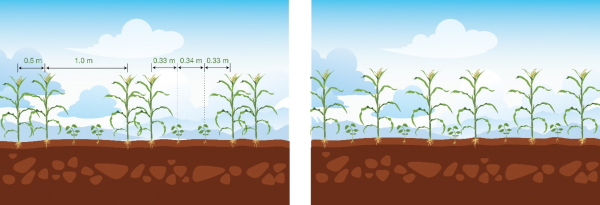

Another major consideration of intercropping is arrangement of crops in the field. A common approach is to alternate one row of maize with one row of a legume, but in Kenya, two rows of a legume alternating with two rows of maize is preferred. This arrangement, known as the MBILI system (mbili meaning “two” in Kiswahili) in Kenya, reduces competition between the maize and legumes, which leads to higher yield for both crops.

CIMMYT promotes the adoption of intercropping and other sustainable agriculture techniques through participatory farmer evaluations (PFEs) eastern and southern Africa. PFEs allow farmers to assess crops at demonstration plots and compare a range of improved seed products against local and traditional seed.

In Makueni County, Kenya, where most farmers grow cereals and legumes together, on-station intercropping trials comprising five drought tolerant maize varieties, six bean varieties and six pigeonpea varieties were set up in 2016 and replicated on several smallholder farmers’ plots. In 2017, the Participatory Evaluation and Application of Climate Smart Agriculture – PEACSA – project invited farmers to score and rate the performance of the crop varieties planted right before harvest time through a PFE.

By comparing crop performance, smallholder farmers are able to see first-hand that when used in combination with improved seed, sustainable techniques like intercropping are key to successful yields and quality seed. Because of this PFEs also create awareness of new products while simultaneously delivering detailed technical knowledge in a more convincing, hands-on manner.

About PEACSA:

Participatory Evaluation and Application of Climate Smart Agriculture (PEACSA) is a flagship project of the Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), in collaboration with different agricultural research organizations, including CIMMYT. Through the PEACSA project a variety of best-bet CSA practices are applied at both on station and on farm levels, in an effort to test and evaluate appropriate technologies to increase agricultural productivity and enhance food security. With participatory evaluation, uptake and adoption of new technologies, especially improved seed varieties, is greatly increased because farmers take stock of the traits that matter to them. Cob size, kernel type, and length of maturity are just some of the characteristics farmers can rate in a participatory evaluation exercise.

About DTMASS:

Led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa Seed Scaling (DTMASS) project works in six countries in eastern and southern Africa to produce and deploy affordable drought tolerant, stress resilient, and high-yielding maize varieties for smallholder farmers. In 2016, DTMASS conducted PFEs in Mozambique and Zambia in collaboration with partners, and aims to conduct dozens more in 2017, across all project target countries.

Climate adaptation and mitigation

Climate adaptation and mitigation