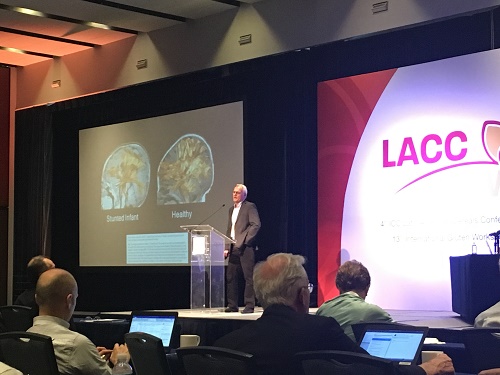

Exposure to more frequent and intense climate extremes is threatening to reverse progress towards ending hunger and malnutrition. New evidence points to rising world hunger. A recent FAO report estimated the number of undernourished people worldwide at over 800 million. Severe food insecurity and undernourishment are increasing in almost all sub-regions of Africa, as well as across South America.

“It’s very important to ensure food security,” says CIMMYT maize quality specialist Natalia Palacios. “But we also have to focus on food nutrition, because increasing yields doesn’t always mean that we’re improving food quality.” Food quality, she explained, is affected not only by genetics, but also by crop and postharvest management practices. As head of CIMMYT’s maize nutritional quality laboratory, Palacios’ work combines research on all three.

As she prepares to attend the World Food Prize in Des Moines, Iowa – which this year recognizes the contributions of those working to combat malnutrition and ensure food and nutrition security – Palacios discusses ways in which she and CIMMYT colleagues work to address health and nutrition challenges.

What role can CIMMYT play in addressing global nutrition challenges?

Nutrition is an interdisciplinary issue, so there are several ways for CIMMYT to engage. In breeding, there’s a lot we can do in biofortification—which means to increase grain nutrient content. The CIMMYT germplasm bank, with its more than 175,000 unique collections of maize and wheat seed, is an invaluable source of genetic traits to develop new nutritious and competitive crops.

CIMMYT also addresses household nutrition challenges, including food availability, proper storage, and consumer behavior and choice. In cropping systems, the Center studies and promotes diversification, agroforestry, and improved soil health and farming practices, and at the landscape level it examines the role of agricultural practices. Gender research and foresight allow us to identify our role in the evolving setting of agri-food systems and rural transformation. We are prioritizing areas where CIMMYT can play a key role to address global nutrition challenges and partner effectively with leading nutrition groups worldwide.

How does the biofortification of staple crops like maize and wheat help to improve nutrition?

CIMMYT biofortification research has focused on micronutrients such as provitamin A in maize and zinc in both maize and wheat, to benefit consumers whose diets depend on those crops and may lack diversity. Biofortification must be complemented by enhanced dietary diversification and education for better nutrition.

How important are processing and post-harvest storage in terms of ensuring high-nutritional quality?

Research on post-harvest processing and storage is key to our work. A critical topic in maize is monitoring, understanding, and controlling aflatoxins—poisonous toxins produced by molds on the grain. CIMMYT has worked mainly to develop aflatoxin-tolerant maize, but recent funding from the Mexican food industry has enabled us to launch a small, more broadly-focused study.

In the past, aflatoxins showed up every three or four years in Mexico, and even then at fairly low levels. Aflatoxin incidence has lately become more frequent, appearing almost every year or two, as climate changes expose crops to higher temperatures and fungi are more likely to develop in the field or storage, especially when storage conditions are poor.

What are the implications of high aflatoxin incidence for health and nutrition?

The implications for health and nutrition are huge. High consumption can affect the immune system and lead to pancreatic and liver cancers, among other grave illnesses.

How easy is it to tell if a kernel is contaminated?

It’s impossible to tell whether grain is contaminated without doing tests. The chemical structure of the toxin includes a lactone ring that fluoresces under UV-light, but this method only tells you whether or not the toxin is present, and results depend contamination levels and kernel placement under the lamp.

We’re spreading the lamp method among farmers so they can detect contamination in their crops, as well as making other of our other methods more accessible and less expensive, for use by farmers and food processors.

Nutrition, health and food security

Nutrition, health and food security