Uganda is one of the fastest economically growing nations in sub-Saharan Africa and is in the midst of socio-economic transition. Over the past two decades the country’s GDP has expanded, on average, by more than 6% each year, with per capita GDP reaching $710 in 2019. Researchers project that this will continue to rise at a rate of 5.6% each year for the next decade, reaching approximately $984 by the year 2031.

This growth is mirrored by a rising population and rapid urbanization within the country. In 2019, 24.4% of the Uganda’s 44.3 million citizens were living in urban areas. By 2030, population is projected to rise to 58-61 million, 31% of whom are expected to live in towns and cities.

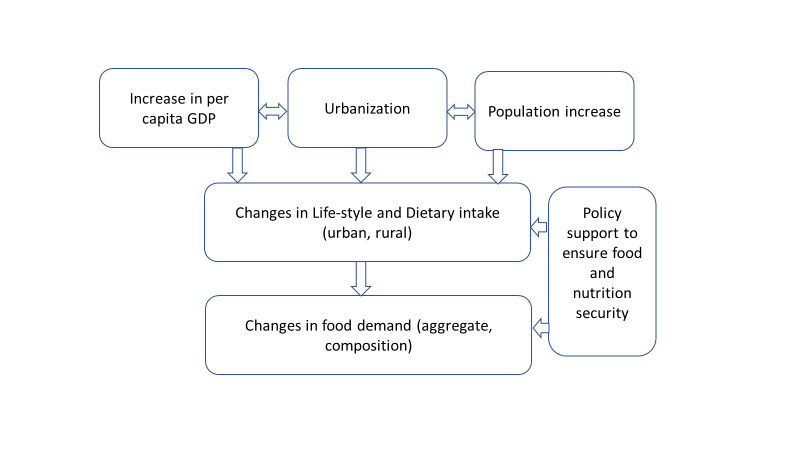

“Changes in population, urbanization and GDP growth rate all affect the dietary intake pattern of a country,” says Khondoker Mottaleb, an economist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). “Economic and demographic changes will have significant impacts on the agricultural sector, which will be challenged to produce and supply more and better food at affordable prices.”

This could leave Uganda in a precarious position.

In a new study, Mottaleb and a team of collaborators project Uganda’s future food demand, and the potential implications for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of zero hunger by 2030.

The authors assess the future demand for major food items, using information from 8,424 households collected through three rounds of Uganda’s Living Standards Measurement Study — Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA). They focus on nationwide demand for traditional foods like matooke (cooking banana), cassava and sweet potato, as well as cereals like maize, wheat and rice — consumption of which has been rising alongside incomes and urbanization.

The study findings confirm that with increases in income and demographic changes, the demand for these food items will increase drastically. In 2018, aggregate consumption was 3.3 million metric tons (MMT) of matooke, 4.7 MMT of cassava and sweet potato, 1.97 MMT of maize and coarse grains, and 0.94 MMT of wheat and rice. Using the Quadratic Almost Ideal Demand System (QUAIDS) estimation approach, the authors show that in 2030 demand could be as high as 8.1 MMT for matooke, 10.5 MMT for cassava and sweet potato, 9.5 MT for maize and coarse grains, and 4 MMT for wheat and rice.

Worryingly, Mottaleb and his team explain that while demand for all the items examined in the study increases, the overall yield growth rate for major crops is stagnating as a result of land degradation, climate extremes and rural out-migration. For example, the yield growth rate for matooke has reduced from +0.21% per year from 1962-1989 to -0.90% from 1990-2019.

As such, the authors call for increased investment in Uganda’s agricultural sector to enhance domestic production capacity, meet the growing demand for food outlined in the study, improve the livelihoods of resource-poor farmers, and eliminate hunger.

Read the full article, Projecting food demand in 2030: Can Uganda attain the zero hunger goal?

Climate adaptation and mitigation

Climate adaptation and mitigation