CIMMYT E-News, vol 3 no. 5, May 2006

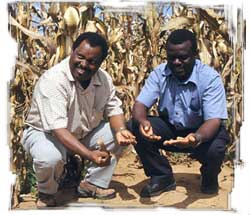

Paul Mapfumo throws his fist into the air and intones, “”Pamberi ne kurima! Pasi neNzara!” Shona for “Forward with agriculture! Down with hunger!” This is the greeting every speaker uses before addressing the gathering of farmers attending a field day in Rusape settlement, eastern Zimbabwe. The 40-odd farmers, young and old, men and women, are united in their desire to learn of ways to rebuild the fertility of their farms’ soils, for better maize harvests. And Mapfumo, the newly appointed coordinator, and members of the Soil Fertility Consortium for Southern Africa (SOFECSA) such as CIMMYT, are determined to help them do just that.

Paul Mapfumo throws his fist into the air and intones, “”Pamberi ne kurima! Pasi neNzara!” Shona for “Forward with agriculture! Down with hunger!” This is the greeting every speaker uses before addressing the gathering of farmers attending a field day in Rusape settlement, eastern Zimbabwe. The 40-odd farmers, young and old, men and women, are united in their desire to learn of ways to rebuild the fertility of their farms’ soils, for better maize harvests. And Mapfumo, the newly appointed coordinator, and members of the Soil Fertility Consortium for Southern Africa (SOFECSA) such as CIMMYT, are determined to help them do just that.

The soils at Rusape are derived from the granite ranges that frame the settlement and are shallow, sandy, and acidic. Their poor water retention capacity makes them prone to waterlogging and leaching during good rains, or drying out completely during the hot season. Maize yields have been falling ever since smallholder farmers were resettled there soon after Zimbabwe’s independence in 1982.

Another recent blow to maize farming at Rusape is the promotion of tobacco farming by the Zimbabwe Tobacco Association, through loans for seed and input purchase. Many farmers, frustrated by poor maize yields and the spiraling cost of inputs, have converted their maize farms to tobacco. But even with the money from their tobacco crop, they are finding they still do not have enough to eat. “From whom do you buy maize when everyone is growing tobacco?” asks Vincent Musindikhwa, an extension agent with the Agricultural Research and Extension (AREX) division. “We’ve had a maize shortage for 4-5 years now, and the granaries are empty.”

Soil infertility is a serious and widespread bottleneck to agricultural development and food security in sub-Saharan Africa. Resource-poor farmers are especially vulnerable, because their plots are traditionally the least fertile, and they lack the money or credit to purchase inorganic fertilizers. Therefore, they stand to benefit the most from the various soil-fertility-improving techniques in SOFECA’s Soil Fertility Management Technologies (SFMT) ‘basket’, particularly those that do not involve a cash outlay, according to CIMMYT economist Mulugetta Mekuria, who assists Mapfumo with SOFECSA management.

The “best bet” soil fertility approaches being promoted—so called because they minimize the risk to farmers—were arrived at by SOFECSA’s predecessor project, SoilFertNet. They include manures (leaf litter, farm, and woodland), inorganic fertilizers, lime, and rotation and intercropping with various legumes and green manure crops (soya bean, sugar bean, sun hemp, mucuna, pigeonpea, groundnut, and cowpea).

Legumes, for example, can fix nitrogen from the air and make it available in the soil. Typical farms in the region have between 3 and 15% of land devoted to legumes. The consortium has determined that increasing the intensity of legume cropping in maize-based systems through systematic rotations and intercrops can provide double the level of nitrogen that is typically provided by the limited use of inorganic fertilizers.

SOFECSA is regional partnership with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and significant in-kind contributions from participants. Its broad membership spans international, national, and regional public and private organizations, including the agriculture ministries of the SADC countries. SOFESCA also works directly with farmers in four southern Africa countries: Zimbabwe, Malawi, Zambia, and Mozambique. Improved maize production is the primary target of consortium’s work, but once soils are fertile, all other crops—and farmers’ lots overall—will benefit. “Our work is a fulcrum for broader NRM problems, and an entry point to solve a spectrum of livelihood issues in the four countries,” says Mapfumo.

Farmers and researchers at the SOFECSA field days engage on topics ranging from crops, soil fertility improvement options, pests, seed, and even markets and pricing. Already, farmers are finding that manuring pays long-lasting dividends. “Manure is a key resource; its effects last up to 3 years,” says Florence Mtambanengwe, a soil scientist at the University of Zimbabwe, one of the SOFECSA partners. The researchers are also finding that liming is a priority for farmers in these acidic soils, and Mapfumo now wants to start discussions involving farmers, researchers, extension workers, and agro-dealers to design a sustainable way to deliver this option to farmers.

By stimulating farmer experimentation and open discussion, SOFECSA is encouraging what Mapfumo terms ”a sense of ownership in the farmers,” and its field sites are taking improved farming practices forward throughout southern Africa, no matter what local language is spoken.

For more information contact Mulugetta Mekuria (m.mekuria@cgiar.org).