The Aral Sea was once the world’s fourth largest inland body of water. But in 1959, Soviet premier Nikita Khruschev unfurled a plan for industrialized agriculture across Central Asia. The government constructed irrigation canals to divert water from the Amu Syr and Amu Darya rivers, the two primary feeders for the Aral Sea, to thirsty cotton fields in Uzbekistan. Today, only about two-fifths of the sea remain. Evaporation exasperated by climate change and pesticide runoff have left the remaining body of water salty and polluted.

The disappearance of the Aral Sea is a tragic story about scaling gone wrong. Larry Cooley, one of the top scaling experts in the world, describes scaling as the attempt to overcome a gap between the need for something and the extent to which that need is being met. In the case of the Aral Sea, the Soviet Union saw a need for more robust cotton production and decided to overcome the gap through large-scale irrigation.

They were successful in reaching their scaling ambition but at a high and unsustainable cost. Would Kruschev still go ahead with his development scheme if he knew it would cause irreversible ecological damage in the future? Would he still prioritize high cotton yields if he knew it would decimate the local fishing industry and leave thousands unemployed?

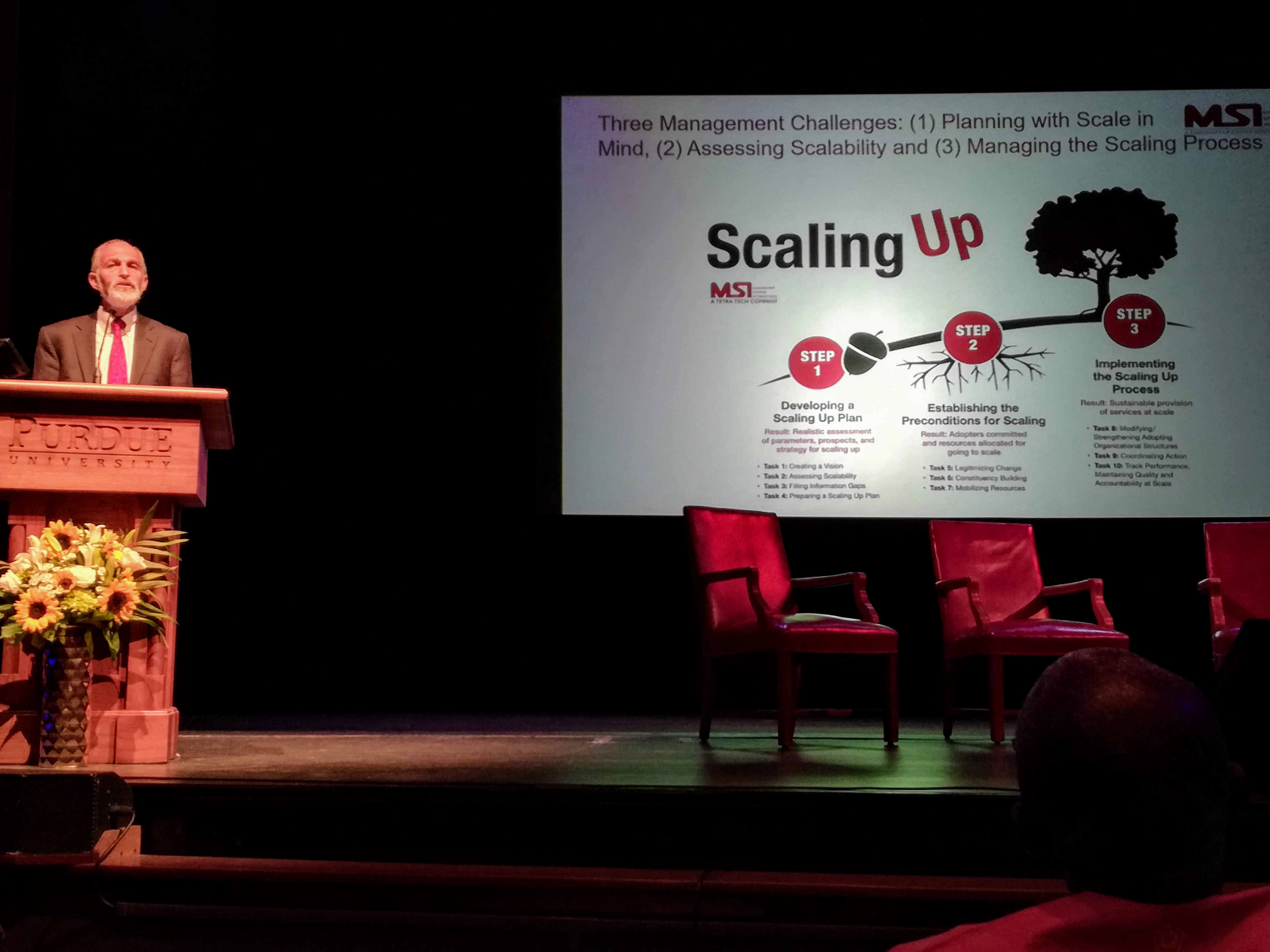

At the recent Scale Up Conference at Purdue University, over 200 researchers and practitioners gathered to discuss effective approaches to scaling up agricultural technologies and innovations in the developing world. The tagline read “Innovations in agriculture: Scaling up to reach millions.” Several of the presenters, however, argued development organizations should think about potential tradeoffs before trying to reach the biggest impact.

Finding the optimal scale

CIMMYT’s scaling advisor Lennart Woltering and mechanization specialist Jelle van Loon led a session on the opportunities and challenges to scaling two-wheeled tractors in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Van Loon explained how mechanization can decrease labor costs, improve livelihoods and help farmers stay locally and internationally competitive, but he acknowledged a few potential downsides. Small tractors of this kind require fossil fuels and maintenance, and introducing mechanization to a rural community has the potential to displace jobs and shift gender roles.

Woltering explained a new tool can help researchers and development organizations think through these tradeoffs in a systematic way. The Scaling Scan, which he developed in a collaboration with The PPPLab, guides users through a series of questions and prompts them to reflect on what scaling means, what it takes to take a project to scale and what the unintended consequences could be in a particular context.

The first step of the Scaling Scan is “Defining a realistic scaling ambition.” It contains a responsibility check, prompting users to consider how an intervention could affect power equity and natural resources if that scaling ambition is indeed reached. “We tried to make this check as simple as possible, but still have people anticipate what unintended consequences their scaling effort might have ten years down the line,” said Woltering.

The responsibility check includes questions like: Who are the winners and who are the losers when the innovation is adopted at a large scale? Will the scaling of the innovation affect the availability of important natural resources, such as water and land?

Woltering emphasized that development organizations should try to identify the scale that optimizes tradeoffs. “We want people to be aware that bigger is not always better,” he said.

“You might think you’re benefitting the irrigation farmers, but at the same time, the fishermen or other people might be paying the price for that,” Woltering explained. “If you’re only focused on those irrigation farmers and not the whole system, it’s easy to think, ‘Oh, we’re doing a fantastic job,’ when you’re not.”

The reasons to scale up responsibly

At the conference, Tricia Wind and Robert McLean of the International Development Research Center (IDRC) presented some of their lessons learned about responsible scaling.

“If you’re working on the problem at different scales, you need to think about the problem differently and think about the solutions differently,” said Wind. “The first principle is thinking about what scale you are starting with and what the optimal scale would be for the problems that you’re focused on solving.”

The second principle is the justification for scaling. “So stepping back from the how and thinking about the why,” she explained. “What difference would this make?” Similar to the responsibility check in the Scaling Scan, the second principle explores the issue of equity. Who would be reached by this solution, and who would be left out or even negatively affected by it?

The third principle is about coordination. McLean said, “This is about accepting that all scaling happens in a system. Are the alternative solutions? How do you displace solutions that might already exist if you try to scale something? What about the cultural norms and the institutions that exist in the area where you’re scaling, and how do you coordinate to scale responsibly?”

The fourth principle is dynamic evaluation. Maclean said an organization should learn as it scales. “It’s never going to be a 1-2-3 step process that’s going to get you from innovation to impact at scale,” he explained. “Scaling itself is also an intervention. So you have your intervention you’re trying to scale, and as you scale, systems change.”

Johannes Linn, Nonresident Senior Fellow with the Brookings Institute and another one of the world’s top scaling experts, emphasized, “Scaling is not a linear process. It is iterative with feedback loops to learn and adapt.”

During the opening reception, Woltering and van Loon congratulated Seerp Wigboldus, a senior advisor and researcher with Wageningen University, on his recently completed PhD thesis, published as a book: To scale, or not to scale – that is not the only question.

Someone asked, “What do you do if 40 people are going to be harmed by an intervention while 50 people benefit?” Wigboldus replied, “Well, unfortunately, there’s no formula for this kind of thing. There will always be tradeoffs, but hopefully we can get people to slow down a bit. We need to be transparent and justify our decisions.”

Nearly all of humanity’s greatest challenges originate from the scaling of innovations. The depletion of the Aral Sea in order to scale cotton production is just one example. Climate change and industrialization is another. By adopting a responsible scaling approach, the agricultural development sector can minimize negative impacts and side effects and seek optimal solutions.

The full version of the Scaling Scan contains detailed practical information on how and when to use this tool. A condensed, two-page version is also available. We also recommend the companion Excel sheet, which generates average scores and results automatically.

This work is supported by the German Development Cooperation (GIZ) and led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

Innovations

Innovations