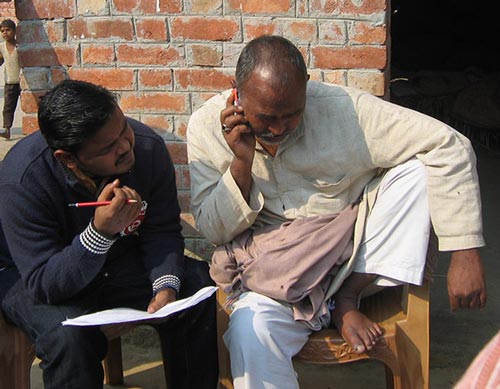

Mobile phones promise new opportunities for reaching farmers with agricultural information, but are their potential fully utilized? CIMMYT’s agricultural economist Surabhi Mittal and IRRI’s economist Mamta Mehar argue that institutional and infrastructural constraints do not allow farmers to take full advantage of this technology. In India, agro-advisory service providers use text and voice messaging along with various mobile phone based applications to provide information about weather, market prices, policies, government schemes, and new technologies. Some service providers, such as IKSL, have reached more than 1.3 million farmers across 18 states of India. But what is the real impact of such services? Are messages available at the right time? Do they create awareness? Do they strengthen farmers’ capability to make informed decisions? Are they relevant to his or her farming context?

Mobile phones promise new opportunities for reaching farmers with agricultural information, but are their potential fully utilized? CIMMYT’s agricultural economist Surabhi Mittal and IRRI’s economist Mamta Mehar argue that institutional and infrastructural constraints do not allow farmers to take full advantage of this technology. In India, agro-advisory service providers use text and voice messaging along with various mobile phone based applications to provide information about weather, market prices, policies, government schemes, and new technologies. Some service providers, such as IKSL, have reached more than 1.3 million farmers across 18 states of India. But what is the real impact of such services? Are messages available at the right time? Do they create awareness? Do they strengthen farmers’ capability to make informed decisions? Are they relevant to his or her farming context?

Mittal and Mehar say there is still a long way to go. While farmers get information through their mobile phones, it is often general information irrespective of their location and crops, which is information they cannot effectively utilize. In 2011, CIMMYT conducted a survey with 1,200 farmers in the Indo-Gangetic Plains; the survey revealed the farmers needed information on how to address pest attacks and what varieties better adapt to changing climatic conditions. Instead, they received standard prescriptions on input use and general seed varietal recommendations. To provide the information farmers really need, dynamic databases with farmers’ land size, cropping pattern, soil type, geographical location, types of inputs used, variety of seed used, and irrigation must be developed.

Sustainability is another problem. Such agro-advisory projects require continued financial assistance; when money runs out, the project ends and the people are again left without information, feeling cheated and without trust for any similar project that may come in the future. There is a need to assess the willingness of farmers to pay for these services and develop sustainable business models, say Mittal and Mehar. Furthermore, it has been shown that the benefits of mobile phone services are not reaching the poor, as they do not have access to the technology despite its increasing availability. The main beneficiaries of the mobile phone revolution are the ones with skills and infrastructure, and the poor are thus left even further behind.

What can be done? Agro-advisory providers need to develop specific, appropriate, and timely content and update it as often as necessary. This cannot be achieved without a thorough assessment of farmers’ needs and their continuous evaluation. To ensure timeliness and accuracy of the provided information, two-way communication is necessary; Mittal and Mehar suggest the creation of helplines to provide customized solutions and enable feedback from farmers. The information delivery must be led by demand, not driven by supply. However, even when all that is done, it must be remembered that merely receiving messages over the phone does not motivate farmers to start using this information. The services have to be supplemented with demonstration of new technologies on farmers’ fields and through field trials.

What can be done? Agro-advisory providers need to develop specific, appropriate, and timely content and update it as often as necessary. This cannot be achieved without a thorough assessment of farmers’ needs and their continuous evaluation. To ensure timeliness and accuracy of the provided information, two-way communication is necessary; Mittal and Mehar suggest the creation of helplines to provide customized solutions and enable feedback from farmers. The information delivery must be led by demand, not driven by supply. However, even when all that is done, it must be remembered that merely receiving messages over the phone does not motivate farmers to start using this information. The services have to be supplemented with demonstration of new technologies on farmers’ fields and through field trials.

For more information, see the full article published on the AESA website. This work is based on the ongoing research at CIMMYT’s Socioeconomics Program funded by CCAFS.

Climate adaptation and mitigation

Climate adaptation and mitigation