Across South Asia, including major wheat-producing regions of India and Pakistan, temperature extremes are threatening wheat production. Heatwaves have been reported throughout the region, with a century record for early onset of extreme heat. Monthly average temperatures across India for March and April 2022 exceeded those recorded over the past 100 years.

Widely recognized as one of the major breadbaskets of the world, the Indo-Gangetic Plains region produces over 100 million tons of wheat annually, from 30 million hectares in Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Pakistan, primarily supporting large domestic demand.

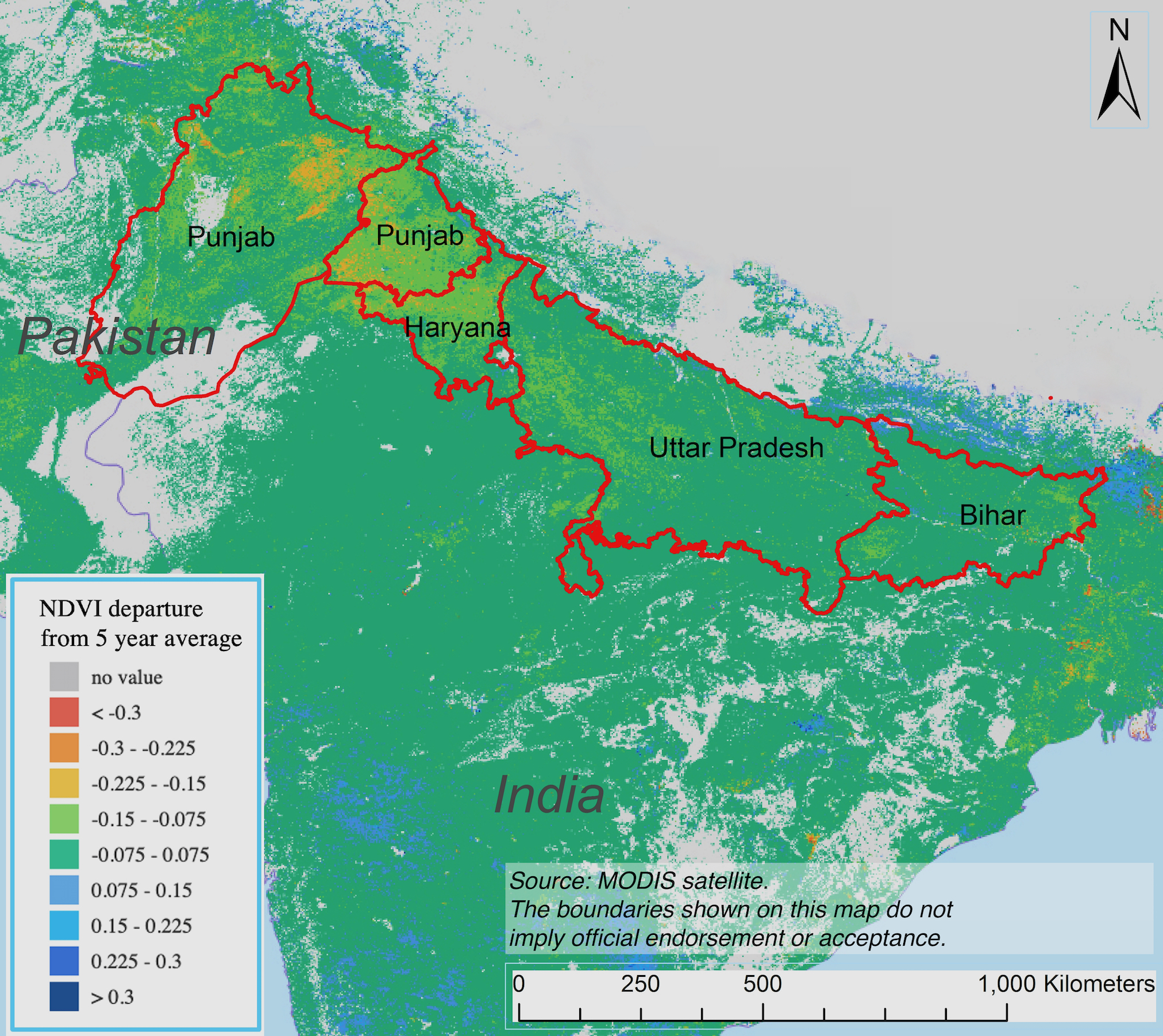

The optimal window for wheat planting is the first half of November. The late onset of the 2021 summer monsoon delayed rice planting and its subsequent harvest in the fall. This had a knock-on effect, delaying wheat planting by one to two weeks and increasing the risk of late season heat stress in March and April. Record-high temperatures over 40⁰C were observed on several days in March 2022 in the Punjabs of India and Pakistan as well as in the state of Haryana, causing wheat to mature about two weeks earlier than usual.

In-season changes and effects

Prior to the onset of extreme heat, the weather in the current season in India was favorable, prompting the Government of India to predict a record-high wheat harvest of 111 million tons. The March heat stress was unexpected and appears to have had a significant effect on the wheat crop, advancing the harvest and likely reducing yields.

In the North-Western Plains, the major wheat basket of India, the area of late-sown wheat is likely to have been most affected even though many varieties carry heat tolerance. Data from CIMMYT’s on-farm experiments show a yield loss between 15 to 20% in that region. The states of Haryana and Punjab together contribute almost 30% of India’s total wheat production and notably contribute over 60% of the government’s buffer stocks. In the North-Eastern Plains, in the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, around 40% of the wheat crop was normal or even early sown, escaping heat damage, whilst the remainder of late-sown wheat is likely to be impacted at a variable level, as most of the crop in this zone matures during the third and fourth week of March.

The Government of India has now revised wheat production estimates, with a reduction of 5.7%, to 105 million tons because of the early onset of summer.

India has reported record yields for the past 5 years, helping it to meet its goal of creating a reserve stock of 40 million tons of wheat after the 2021 harvest. It went into this harvest season with a stock of 19 million tons, and the country is in a good position to face this year’s yield loss.

In Pakistan, using satellite-based crop monitoring systems, the national space agency Space & Upper Atmosphere Research Commission (SPARCO) estimated wheat production reduction close to 10%: 26 million tons, compared to the production target of 29 million tons, for the 2021-22 season.

Rural and farming health impacts

Alongside a direct negative impact on agricultural productivity, the extreme temperatures in South Asia are likely to have negative health implications for the large rural labor force involved in wheat production. There is a growing body of evidence documenting declining health status in the agricultural workforce in areas of frequent temperature extremes. This also adds to the substantial human and environmental health concerns linked to residue burning.

We recommend that systematic research be urgently undertaken to characterize and understand the impacts of elevated temperatures on the health of field-based workers involved in wheat production. This is needed to develop a holistic strategy for adapting our global cropping systems to climate change.

Amplifying wheat supply risks

Combined with the wheat supply and price impacts of the current conflict in Ukraine and trade restrictions on Russian commodities, these further impacts on the global wheat supply are deeply troubling.

India had pledged to provide increased wheat exports to bolster global supplies, but this now looks uncertain given the necessity to safeguard domestic supplies. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indian government supported domestic food security by providing free rations — mainly wheat and rice — to 800 million people over several months. This type of support relies on the availability of large buffer stocks which appear stable, but may be reduced if grain production and subsequent procurement levels are lower than desired.

We are already seeing indications of reduced procurement by governments with market prices running higher than usual. However, although the Food Corporation of India has procured 27% less wheat grain in the first 20 days of the wheat procurement season compared to the same period last year, the Government of India is confident about securing sufficient wheat buffer stocks.

As with the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, it is likely that the most marked effects of both climate change and shortages of staple crops will hit the poorest and most vulnerable communities hardest.

A chain reaction of climate impacts

The real impacts of reduced wheat production due to extreme temperatures in South Asia demonstrate the realities of the climate emergency facing wheat and agricultural production. Direct impacts on farming community health must also be considered, as our agricultural workforce is pushed to new physical limits.

Anomalies, which are likely to become the new normal, can set off a chain reaction as seen here: the late onset of the summer monsoon caused delays in the sowing of rice and the subsequent wheat crop. The delayed wheat crop was hit by the unprecedented heatwave in mid- to late March at a relatively earlier stage, thus causing even more damage.

Preparing for wheat production tipping points

Urgent action is required to develop applied mitigation and adaptation strategies, as well as to plan for transition and tipping points when key staple crops such as wheat can no longer be grown in traditional production regions.

A strategic design process is needed, supported by crop and climate models, to develop and test packages of applied solutions for near-future climate changes. On-farm evidence from many farmers’ fields in Northwestern India indicates that bundled solutions — no-till direct seeding with surface retention of crop residues coupled with early seeding of adapted varieties of wheat with juvenile heat tolerance — can help to buffer terminal heat stress and limit yield losses.

Last but not least, breeding wheat for high-temperature tolerance will continue to be crucial for securing production. Strategic planning needs to also encompass the associated social, market and political elements which underpin equitable food supply and stability.

Download the pre-print:

Wheat vs. Heat: Current temperature extremes threaten wheat production in South Asia

Innovations

Innovations