One of the strongest El Niños on record is underway, threatening millions of agricultural livelihoods – and lives.

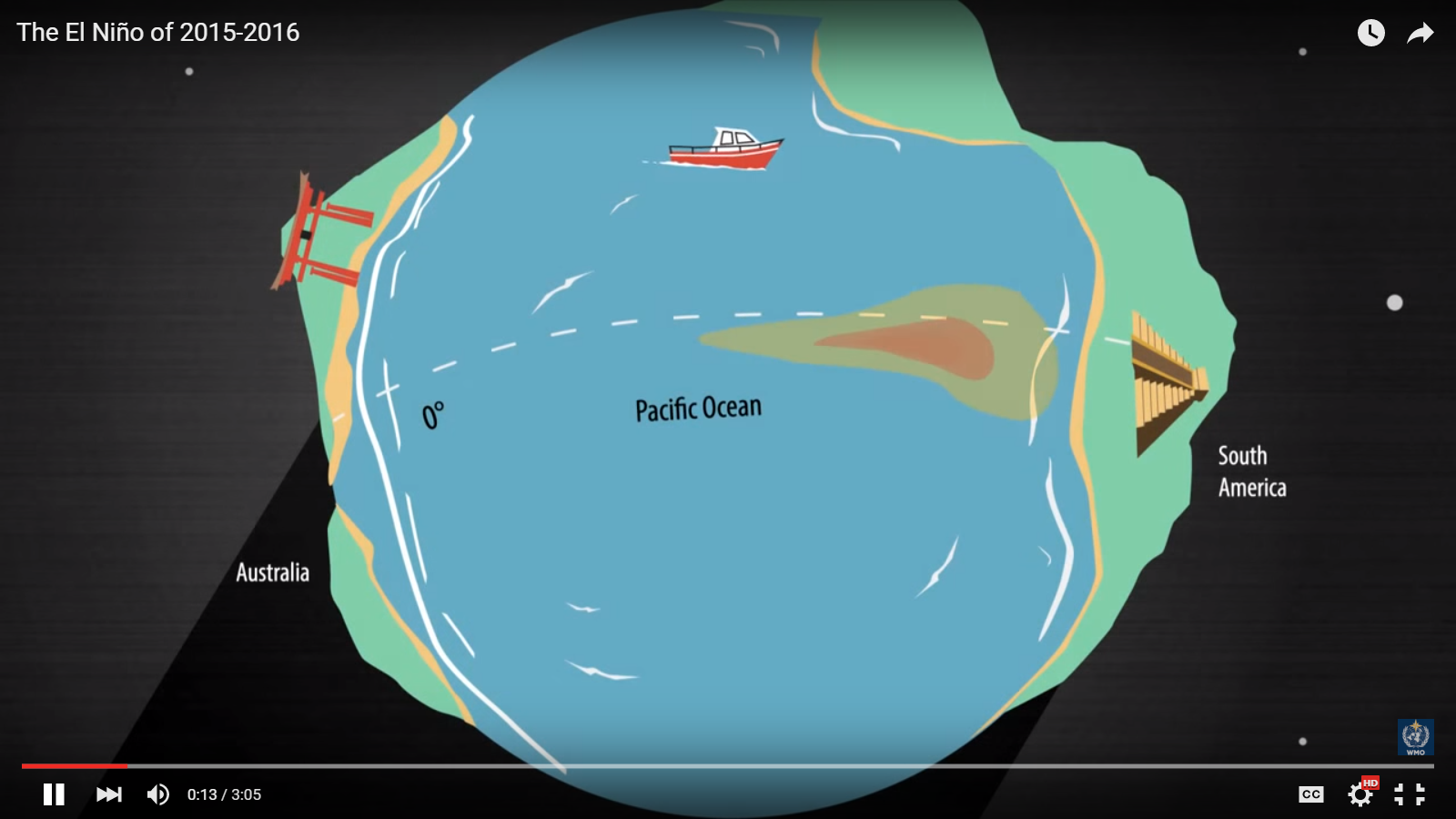

At least ten million people in the developing world are facing hunger due to droughts and erratic rainfall as global temperatures reach new records coupled with the onset of a powerful El Niño – the climate phenomenon that develops in the tropical Pacific and brings extreme weather across the world. Warmer than usual waters in the Pacific have made this year’s El Niño a contender for the strongest on record, currently held by the 1997 El Niño, which caused over $35 billion in global economic losses and claimed an estimated 23,000 lives. These extreme El Niños are twice as likely to occur due to climate change, according to a letter published in Nature magazine by researchers at McGill University, Montreal, Canada, and the University of Sussex, Brighton, UK.

Who is most at risk?

Nearly 40 million people will be in need of emergency food assistance this year – a 30 percent increase over previous estimates – due in large part to added stress from El Niño, according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC).

This El Niño has resulted in severe drought throughout Central America, the Caribbean and Ethiopia, and is predicted to lead to flooding in the Horn of Africa and drought in southern Africa in the coming months. It has also disrupted the Indian monsoon and led to drier conditions in Southeast Asia and Indonesia, which has resulted in devastating wildfires across the country.

The El Niño phenomenon is often followed by a transition to La Niña, another driver of global weather patterns. If this were to happen again, it would mean more severe drought in the eastern Horn of Africa, and hurt crops like sugar, palm oil, and rice in Asia.

Responding to and mitigating El Niño’s effects

Ensuring farmers are equipped with climate resilient varieties that can withstand extreme stresses such as drought or waterlogging is an essential measure to counteract the side effects of El Niño. For example, after planting a drought tolerant maize variety developed by CIMMYT, farmers in Tanzania produced nearly 50 percent more grain than they normally would under the same conditions using other commercial varieties. In South Asia, CIMMYT has developed maize varieties that are tolerant to waterlogging and provide a safety net in years with heavy rains or flooding.

Equipping farmers with good agronomic practices and tools to reap the benefits of these crops is equally important. Ensuring farmers adjust planting times is critical for crops to adapt to changing weather patterns, while smart water management practices such as no-till farming can help raise wheat yields while reducing water and fuel costs. Precision land levelers – machines that level fields so water flows evenly into soil, rather than running off or collecting in uneven land – have enabled farmers in South Asia to save up to 30 percent more water, use less fertilizer and produce more grain yield.

Crop-index insurance is another tool that can serve as both a preventive and responsive measure to support smallholders during natural disasters. It allows farmers to purchase coverage based on an index that is correlated with those losses, such as average yield losses over a larger area or a well-defined climate risk – like drought – that significantly influences crop yields. If implemented correctly, index insurance can build resilience for smallholder farmers not only by ensuring a payout in the event of climate shocks like those caused by El Niño, but also by giving farmers the incentive to invest in new technology and inputs, such as seed.

So – are we prepared for this storm? Since 2003, nearly one-quarter of all damage and losses from climate-related disasters have occurred in the agricultural sector in developing countries. While global food security will likely not suffer another shock like that of 2007-08, primarily because global stocks of maize, wheat and rice are so large, natural disasters resulting from El Niño combined with climate change are playing out into unchartered territory, posing a real threat to people’s lives and livelihoods.

This isn’t the time to be complacent. We need to take preventive measures, and long-term investments in agricultural research will help us be prepared for future shocks and ensure crops and livelihoods can withstand more frequent natural disasters.

Capacity development

Capacity development