HARARE (CIMMYT) — In southern Africa close to 50 million people are projected to be affected by droughts caused by the current El Niño, a climate phenomenon that develops in the tropical Pacific Ocean causing extreme weather worldwide — this year, one of the strongest on record. Many of those millions are expected to be on the brink of starvation and dependent on emergency food aid and relief.

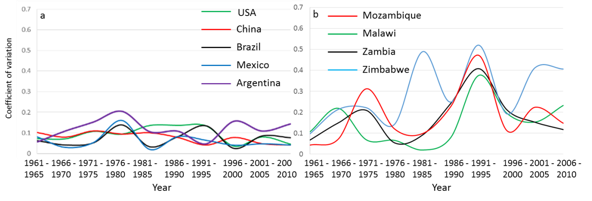

However, severe droughts are nothing new to the region. Between 1900 and 2013 droughts have killed close to 1 million people in Africa, with economic damages of about $3 billion affecting over 360 million people. Over the past 50 years, 24 droughts have been caused by El Niño events, according to research by Ilyas Masih. If droughts are so recurrent and known to be a major cause of yield variability and food insecurity in southern Africa, why are we still reacting to this as a one-time emergency instead of a calculated threat?

Over the past 50 years, donors have focused on the “poorest of the poor” in agriculture – areas where farming is difficult due to low and erratic rainfalls, poor sandy soils and high risk of crop failure. Investments were made in these areas to change farmers’ livelihoods – and yet the numbers of food insecure people are the same or rising in many southern African countries. Once drought hits, most farmers are left with no crops and are forced to sell their available livestock. Due to many farmers flooding the market with poor meat at once, prices for both livestock and meat hit rock bottom. Only when the situation becomes unbearable does the development community act, calling for emergency aid, which kicks in with a stuttering start. Abject poverty and food aid dependency is the inevitable consequence.

Short-term relief can help millions of farmer families in this current crisis, and emergency solutions will likely be necessary this year. However, emergency relief is not the solution to saving lives and money in a world where extreme weather events are only going to become more frequent.

We know that the next drought will come within the next two to three years.

Proactive, strategic and sustainable response strategies are needed to increase farming system resilience and reduce dependency on food aid during extreme weather events like El Niño. This starts with improving the capacity of local, regional and national governments to make fully informed decisions on how to prepare for these events. Interventions must reach beyond poor performing areas, but also support higher productivity areas and emerging commercial farmers, who have greater potential to produce enough grain on a national scale to support areas hardest hit by droughts and dry-spells.

Climate-smart agriculture technologies, drought-tolerant maize, and such techniques as conservation agriculture, agroforestry and improved soil fertility management are approaches to farming that seek to increase food and nutrition security, alleviate poverty, conserve biodiversity and safeguard ecosystem services.

They need to be scaled out to increase resilience to climate variability. This strategy of improved foresight and targeting coupled with adoption of climate-smart agriculture and improved outscaling can lead to increased resilience of smallholder farming systems in southern Africa, reducing year-to-year variability and the need for emergency response.

Learn more about the impacts of El Niño and building resilience in the priority briefing “Combating drought in southern Africa: from relief to resilience” here, and view the special report from FEWS Net illustrating the extent and severity of the 2015-16 drought in southern Africa.

Climate adaptation and mitigation

Climate adaptation and mitigation