The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) coordinated the VIII International Cereal Nematode Symposium between September 26-29, in collaboration with the Turkish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, the General Directorate of Agricultural Research and Policies and Bolu Abant Izzet Baysal University.

As many as 828 million people struggle with hunger due to food shortages worldwide, while 345 million are facing acute food insecurity – a crisis underpinning discussions at this symposium in Turkey focused on controlling nematodes and soil-borne pathogens causing reduced wheat yields in semi-arid regions.

A major staple, healthy wheat crops are vital for food security because the grain provides about a fifth of calories and proteins in the human diet worldwide.

Seeking resources to feed a rapidly increasing world population is a key part of tackling global hunger, said Mustafa Alisarli, the rector of Turkey’s Bolu Abant Izzet Baysal University in his address to the 150 delegates attending the VIII International Cereal Nematode Symposium in the country’s province of Bolu.

Suat Kaymak, Head of the Plant Protection Department, on behalf of the director general of the General Directorate of Agricultural Research and Policies (GDAR), delivered an opening speech, emphasizing the urgent need to support the CIMMYT Soil-borne Pathogens (SBP) research. He stated that the SBP plays a crucial role in reducing the negative impact of nematodes and pathogens on wheat yield and ultimately improves food security. Therefore, the GDAR is supporting the SBP program by building a central soil-borne pathogens headquarters and a genebank in Ankara.

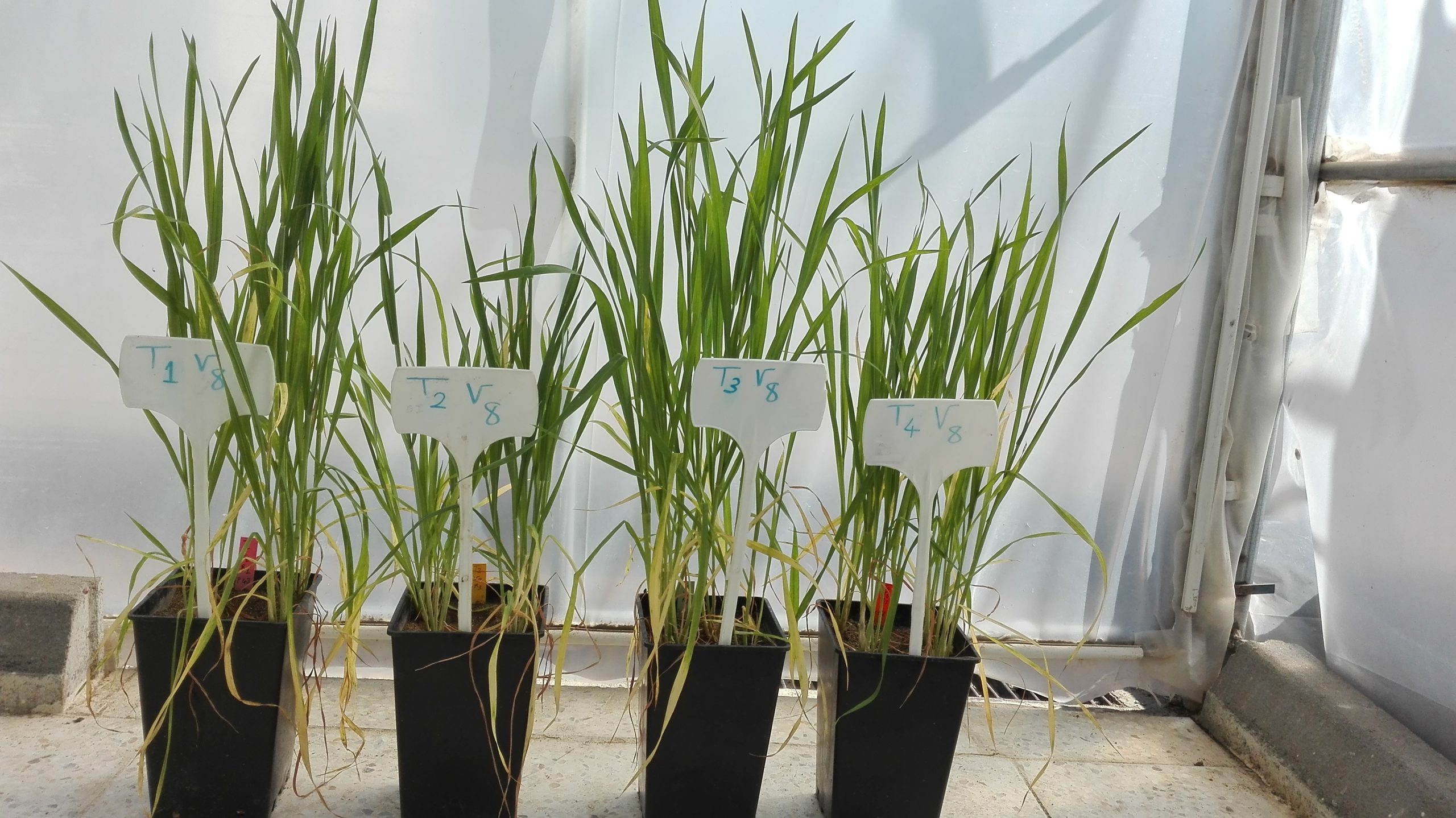

Discussions during the five-day conference were focused on strategies to improve resilience to the Cereal Cyst Nematodes (Heterodera spp.) and Root Lesion Nematodes (Pratylenchus spp.), which cause root-health degradation, and reduce moisture uptake needed for proper development of wheat.

Richard Smiley, a professor emeritus at Oregon State University, summarized his research on nematode diseases. He has studied nematodes and pathogenic fungi that invade wheat and barley roots in the Pacific Northwest of the United States for 40 years. “The grain yield gap – actual versus potential yield – in semiarid rainfed agriculture cannot be significantly reduced until water and nutrient uptake constraints caused by nematodes and Fusarium crown rot are overcome,” he said.

Experts also assessed patterns of global distribution, exchanging ideas on ways to boost international collaboration on research to curtail economic losses related to nematode and pathogen infestations.

A special session on soil-borne plant pathogenic fungi drew attention to the broad spectrum of diseases causing root rot, stem rot, crown rot and vascular wilts of wheat.

Soil-borne fungal and nematode parasites co-exist in the same ecological niche in cereal-crop field ecosystems, simultaneously attacking root systems and plant crowns thereby reducing the uptake of nutrients, especially under conditions of soil moisture stress.

Limited genetic and chemical control options exist to curtail the damage and spread of these soil-borne problems which is a challenge exacerbated by both synergistic and antagonistic interactions between nematodes and fungi.

Nematodes, by direct alteration of plant cells and consequent biochemical changes, can predispose wheat to invasion by soil borne pathogens. Some root rotting fungi can increase damage due to nematode parasites.

Integrated managementFor a holistic approach to addressing the challenge, the entire biotic community in the soil must be considered, said Hans Braun, former director of the Global Wheat Program at CIMMYT.

Braun presented efficient cereal breeding as a method for better soil-borne pathogen management. His insights highlighted the complexity of root-health problems across the region, throughout Central Asia, West Asia and North Africa (CWANA).

Richard A. Sikora, Professor emeritus and former Chairman of the Institute of Plant Protection at the University of Bonn, stated that the broad spectrum of nematode and pathogen species causing root-health problems in CWANA requires site-specific approaches for effective crop health management. Sikora added that no single technology will solve the complex root-health problems affecting wheat in the semi-arid regions. To solve all nematode and pathogen problems, all components of integrated management will be needed to improve wheat yields in the climate stressed semi-arid regions of CWANA.

Building on this theme, Timothy Paulitz, research plant pathologist at the United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service (USDA-ARS), presented on the relationship between soil biodiversity and wheat health and attempts to identify the bacterial and fungal drivers of wheat yield loss. Paulitz, who has researched soil-borne pathogens of wheat for more than 20 years stated that, “We need to understand how the complex soil biotic ecosystem impacts pathogens, nutrient uptake and efficiency and tolerance to abiotic stresses.”

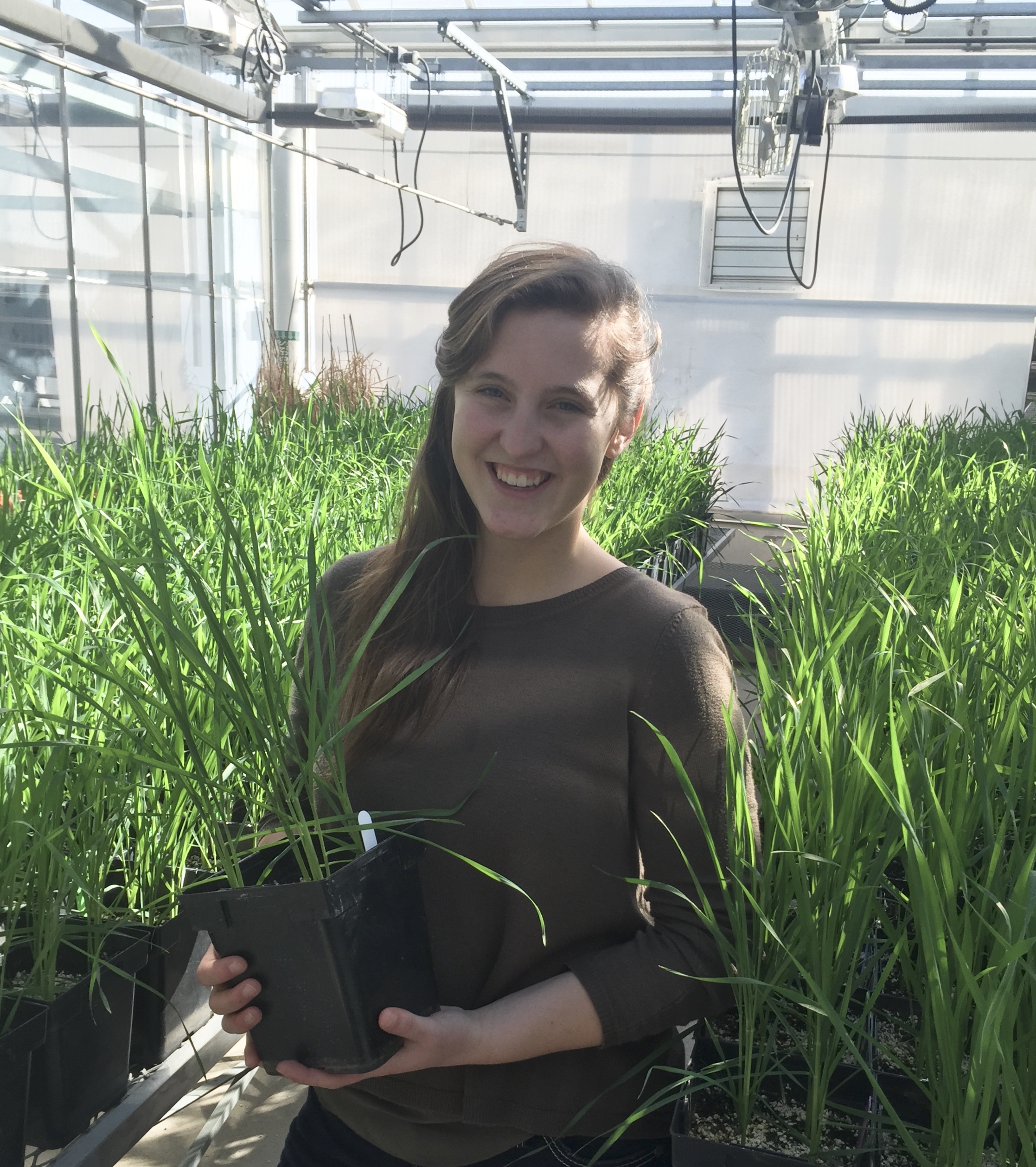

Julie Nicol, former soil-borne pathologist at CIMMYT, who now coordinates the Germplasm Exchange (CAIGE) project between CIMMYT and the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) at the University of Sydney’s Plant Breeding Institute, pointed out the power of collaboration and interdisciplinary expertise in both breeding and plant pathology. The CAIGE project clearly demonstrates how valuable sources of multiple soil-borne pathogen resistance in high-yielding adapted wheat backgrounds have been identified by the CIMMYT Turkey program, she said. Validated by Australian pathologists, related information is stored in a database and is available for use by Australian and international breeding communities.

Economic losses

Root-rotting fungi and cereal nematodes are particularly problematic in rainfed systems where post-anthesis drought stress is common. Other disruptive diseases in the same family include dryland crown and the foot rot complex, which are caused mainly by the pathogens Fusarium culmorum and F. pseudograminearum.

The root lesion nematode Pratylenchus thornei can cause yield losses in wheat from 38 to 85 percent in Australia and from 12 to 37 percent in Mexico. In southern Australia, grain losses caused by Pratylenchus neglectus ranged from 16 to 23 percent and from 56 to 74 percent in some areas.

The cereal cyst nematodes (Heterodera spp.) with serious economic consequences for wheat include Heterodera avenae, H. filipjevi and H. latipons. Yield losses due to H. avenae range from 15 to 20 percent in Pakistan, 40 to 92 percent in Saudi Arabia, and 23 to 50 percent in Australia.

In Turkey, Heterodera filipjevi has caused up to 50 percent crop losses in the Central Anatolia Plateau and Heterodera avenae has caused up to 24 percent crop losses in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The genus Fusarium which includes more than a hundred species, is a globally recognized plant pathogenic fungal complex that causes significant damage to wheat on a global scale.

In wheat, Fusarium spp. cause crown-, foot-, and root- rot as well as head blight. Yield losses from Fusarium crown-rot have been as high as 35 percent in the Pacific Northwest of America and 25 to 58 percent in Australia, adding up losses annually of $13 million and $400 million respectively, due to reduced grain yield and quality. The true extent of damage in CWANA needs to be determined.

Abdelfattah Dababat, CIMMYT’s Turkey representative and leader of the soil-borne pathogens research team said, “There are examples internationally, where plant pathologists, plant breeders and agronomists have worked collaboratively and successfully developed control strategies to limit the impact of soil borne pathogens on wheat.” He mentioned the example of the development and widespread deployment of cereal cyst nematode resistant cereals in Australia that has led to innovative approaches and long-term control of this devastating pathogen.

Dababat, who coordinated the symposium for CIMMYT, explained that, “Through this symposium, scientists had the opportunity to present their research results and to develop collaborations to facilitate the development of on-farm strategies for control of these intractable soil borne pathogens in their countries.”

Paulitz stated further that soil-borne diseases have world-wide impacts even in higher input wheat systems of the United States. “The germplasm provided by CIMMYT and other international collaborators is critical for breeding programs in the Pacific Northwest, as these diseases cannot be managed by chemical or cultural techniques,” he added.

Road ahead

Delegates gained a greater understanding of the scale of distribution of cereal cyst nematodes and soil borne pathogens in wheat production systems throughout West Asia, North Africa, parts of Central Asia, Northern India, and China.

After more than 20 years of study, researchers have recognized the benefits of planting wheat varieties that are more resistant. This means placing major emphasis on host resistance through validation and integration of resistant sources using traditional and molecular methods by incorporating them into wheat germplasm for global wheat production systems, particularly those dependent on rainfed or supplementary irrigation systems.

Sikora stated that more has to be done to improve Integrated Pest Management (IPM), taking into consideration all tools wherever resistant is not available. Crop rotations for example have shown some promise in helping to mitigate the spread and impact of these diseases.

“In order to develop new disease-resistant products featuring resilience to changing environmental stress factors and higher nutritional values, modern biotechnology interventions have also been explored,” Alisarli said.

Brigitte Slaats and Matthias Gaberthueel, who represent Swiss agrichemicals and seeds group Syngenta, introduced TYMIRIUM® technology, a new solution for nematode and crown rot management in cereals. “Syngenta is committed to developing novel seed-applied solutions to effectively control early soil borne diseases and pests,” Slaats said.

It was widely recognized at the event that providing training for scientists from the Global North and South is critical. Turkey, Austria, China, Morocco, and India have all hosted workshops, which were effective in identifying the global status of the problem of cereal nematodes and forming networks and partnerships to continue working on these challenges.

Capacity development

Capacity development