Edward Mabaya is a Research Associate in the Department of Applied Economics and Management at Cornell University and a development practicioner. All views expressed are his own.

There are many crops that conjure up an image of the African continent – maize, sorghum, millet, turf, matoke and cassava. These staples form the basis of African’s daily diet and have been established over many years through close interaction between culture and agro-ecological conditions.

Yet there is one less talked about food that you will find in every African urban area. Bread.

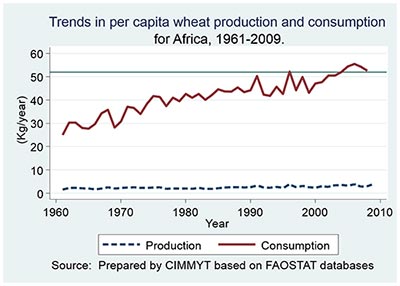

In 2013, African countries spent about $12 billion dollars to import 40 million metric tons of wheat, equating to about a third of the continent’s food imports. This arises as a result of the fact that only 44% of Africa’s wheat demand is met by local production. The only country on the continent with a significant production base is South Africa with over 2 million metric tons per year.

As if the current deficit was not bad enough, the demand for wheat in Africa is growing at a faster rate than for any other crop. By 2050, wheat imports are anticipated to increase by a further 23.1 million metric tons. In the last 20 years wheat imports have increased fourfold from about $3 billion in 1989 and doubled from a rate of $5 billion in 2005 (see table below). This demand is being driven by population growth, urbanization, as well as from a growing female work force who prefer wheat products, like bread or pasta, because they are faster and easier to prepare than traditional foods.

What can African countries do to reduce their wheat imports?

A short-term measure is to mandate or promote the use of composite flours that mix wheat with locally abundant starches such as cassava and starchy bananas (matoke). This practice is already in place in some countries. Nigeria, for example, mandates flour millers to include five percent cassava flour in wheat flour. Tooke flour, developed by Uganda’s Presidential initiative on Banana Industrial Development (PIBID) shows some promise. However, composite flours are only a Band-Aid solution to the growing demand for wheat based products especially given the fact that you can only substitute up to 5% before quality diminishes significantly. The only viable long-term solution is for African countries to meet a large portion of domestic demand through local production.

Like most of my African colleagues, I have always unquestioningly assumed an agronomic basis for Africa’s wheat import, that wheat is a northern hemisphere crop that does not grow well in Africa. A 2012 joint study by CIMMYT and IFPRI exploring “The Potential for Wheat Production in Africa” was an eye opener for me. Based on an integrated biological and economic simulation-based model for 12 countries, the study concluded that Africa has great potential to produce wheat in an economically viable way. The limiting factors, it turns out, are more to do with policy, institutional and social-cultural environments than agro-ecological ones. One example of which is that the heavy subsidies on wheat imports by most African governments have crowded out potential investment in domestic wheat production.

The good news is that enabling policy and institutional environments are cheaper to fix and more environmentally sustainable than making agro-ecological adaptations. The not so good news is that decades of history will be difficult to change – importing wheat is a lucrative business with strong political ties. Boosting Africa’s wheat production will require a coordinated approach with a range of partners to build the requisite enabling environment. This will need more investment in research and development, improved research infrastructure, better agricultural extensions, effective farmer associations and farmer training, better storage and improved access to affordable high quality agro-inputs (seed, fertilizers, chemicals, and machinery).

This enabling environment for wheat production in Africa will not be achieved overnight. It will take years of coordinated strategic investments and policy transformation. Key policy makers on the continent are making the first steps. In 2012, the Joint African Ministers of Agriculture and Trade “endorsed wheat as one of Africa’s strategic commodities for achieving food and nutrition security” at a meeting held in Addis Ababa. A high level Forum for Agricultural Research in Africa (FARA) meeting held in Accra in July 2013 developed a strategy for promoting African wheat production. It is especially encouraging that African governments have chosen a regional approach and multi-stakeholder approach to lower the continent’s wheat imports.

As the old African saying goes: “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.”

Nutrition, health and food security

Nutrition, health and food security