Five international wheat research teams have been awarded grants for their proposals to boost climate resilience in wheat through discovery and development of new breeding technologies, screening tools and novel traits.

Wheat is one of the world’s most important staple crops, accounting for about 20% of all human calories and protein and is increasingly threatened by the impacts of climate change. Experts around the world are working on ways to strengthen the crop in the face of increasing heat and drought conditions.

The proposals were submitted in response to a call by the Heat and Drought Wheat Improvement Consortium (HeDWIC), led by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and global partners, made in 2021.

The grants were made possible by co-funding from the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR) and in-kind contributions from awardees as part of a project which brings together the latest research from scientists across the globe to deliver climate resilient wheat to farmers as quickly as possible.

Cutting-edge wheat research

Owen Atkin, from the Centre for Entrepreneurial Agri-Technology at the Australian National University, leads the awarded project “Discovering thermally stable wheat through exploration of leaf respiration in combination with photosystem II capacity and heat tolerance.”

“The ratio of dark respiration to light and CO2 saturated photosynthesis is a clear indicator of the respiratory efficiency of a plant,” Atkin said. “We will measure and couple this indicator of respiratory efficiency to the leaf hyperspectral signature of field grown wheat exposed to heat and drought. The outcome could be a powerful tool which is capable of screening for wheat lines that are more productive when challenged with drought and heatwave.”

Hannah M. Schneider, of Wageningen University & Research, leads the awarded project examining the use of a novel root trait called Multiseriate Cortical Sclerenchyma to increase drought-tolerance in wheat.

“Drought is a primary limitation to global crop production worldwide. The presence of small outer cortical cells with thick, lignified cell walls (MCS: Multiseriate Cortical Sclerenchyma) is a novel root trait that has utility in drought environments,” Schneider said. “The overall objective of this project is to evaluate and develop this trait as a tool to improve drought resistance in wheat and in other crops.”

John Foulkes, of the University of Nottingham, leads an awarded project titled “Identifying spike hormone traits and molecular markers for improved heat and drought tolerance in wheat.”

“The project aims to boost climate-resilience of grain set in wheat by identifying hormone signals to the spike that buffer grain set against extreme weather, with a focus on cytokinin, ABA and ethylene responses,” Foulkes said. “This will provide novel phenotyping screens and germplasm to breeders, and lay the ground-work for genetic analysis and marker development.”

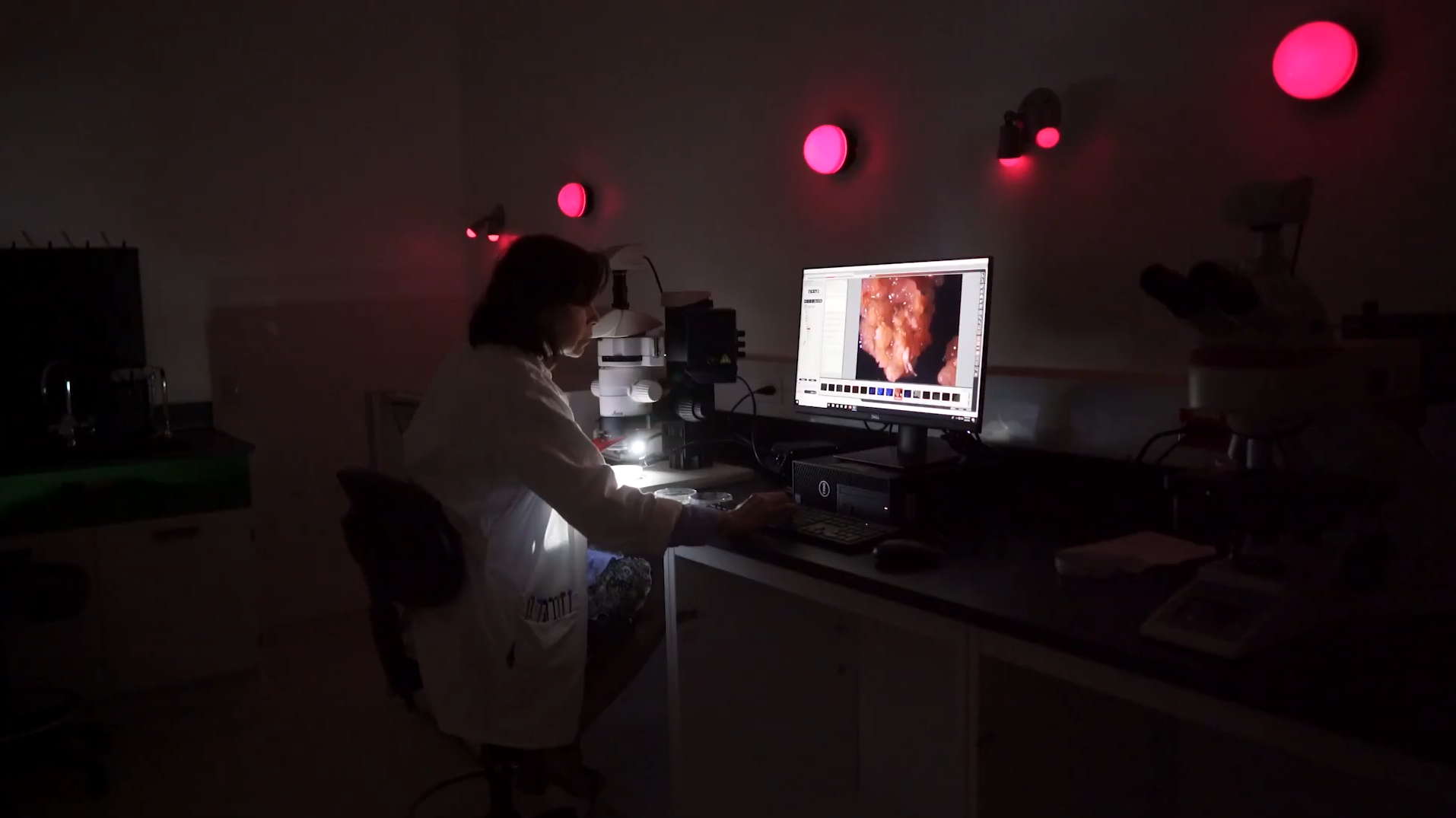

Erik Murchie, from the University of Nottingham, leads an awarded project to explore new ways of determining genetic variation in heat-induced growth inhibition in wheat.

“High temperature events as part of climate change increasingly limit crop growth and yield by disrupting metabolic and developmental processes. This project will develop rapid methods for screening growth and physiological processes during heat waves, generating new genetic resources for wheat,” Murchie said.

Eric Ober of the National Institute of Agricultural Botany in the UK, leads the awarded project “Targeted selection for thermotolerant isoforms of starch synthase.”

“Wheat remains a predominant source of calories and is fundamental to regional food security around the world. It is urgent that breeders are equipped to produce new varieties with increased tolerance to heat and drought, two stresses that commonly occur together, limiting grain production. The formation and filling of grain depends on the synthesis of starch, but a key enzyme in the pathway, starch synthase, is particularly sensitive to temperatures over 25°C. However, there exist forms of this enzyme that exhibit greater thermotolerance than that found in most current wheat varieties,” Ober said. “This project aims to develop a simple assay to screen diverse germplasm for sources of more heat-resistant forms of starch synthase that could be bred into new wheat varieties in the future.”

Breakthroughs from these projects are expected to benefit other crops, not just wheat. Other benefits of the projects include closer interaction between scientists and breeders and capacity building of younger scientists.

Climate adaptation and mitigation

Climate adaptation and mitigation