Lack of good seed of appropriate varieties is holding back harvests of smallholder wheat farmers in rugged, rain-fed areas of Punjab, Pakistan, said a group of farmers to some 50 representatives of seed companies, input dealers, and research, extension and development organizations, at a workshop in Chakwal, Punjab, on 18 September 2014.

“Ninety-five percent of farmers in Pothwar, a semi-arid region of bare and broken terrain, use farm-saved seed of obsolete varieties, invariably with limited use of modern agricultural technologies and inputs, resulting in poor crop establishment and low yields,” said Krishna Dev Joshi, CIMMYT wheat improvement specialist based in Pakistan. “Their yields average only 0.6 tons per hectare, whereas progressive farmers in irrigated areas get ten times that much.”

Joshi said only three varieties cover 83 percent of the region’s wheat area and the same cultivars have been used for an average of 24 years. “One of these, C591, is a variety that was recommended in 1934 and is still grown on about 14 percent of the region’s nearly 0.6 million hectares of wheat area.”

According to Akhlaq Hussain, ex-Director General, Pakistan Department of Federal Seed Certification and Registration, one problem is that, despite their low yields, the older varieties have many traits that the farmers like. For example, they give stable yields under low inputs and harsh growing conditions and provide the preferred flavor and long-lasting good texture in chapattis.

Muhammad Tariq, Director of the Barani Agricultural Research Institute (BARI), Chakwal, Punjab, said there are few producers or suppliers of suitable, quality seed, fertilizer or other farm inputs for such marginal areas. They may be considered unattractive markets, but more than 70 percent of Pakistani wheat farmers are smallholders, cultivating between one and five hectares of land, according to Tariq.

Such farmers harvest on average only 1.5 tons per hectare and urgently need better seed and technology to raise their yields, said Joshi. “Farmers at the workshop complained they could not get access to high-yielding varieties of their choice,” he explained. “They also criticized the long time — typically three years — required to obtain seed of new varieties, once the varieties are officially released.”

Given this need and the lack of legitimate suppliers, fraudulent seed dealers and middlemen often market inferior or false products. “Last year I bought a bag of seed labelled ‘Galaxy,’ a new, high-yielding variety,” said Haji Muhammad Aslam Ochallee, a farmer from Khushab District, “but the seed inside was of an entirely different variety.”

Some seed dealers may mix seed or sell grain in bags labelled ‘certified seed’ at low prices to lure smallholders, and big landlords may sell cheap seed illegally to neighbors, said Qaiser Rasheed, Managing Director of the company Robert Cotton Association. “All these practices cheat farmers, distort markets and erode farmers’ trust in the formal seed sector,” Rasheed observed.

Pothwar’s problems reflect Pakistan’s overall food security challenge, according to Joshi. “A 2014 bulletin by the World Food Program shows that more than 27 million people in Pakistan are highly-to-severely food insecure,” he said. “The big concern is that most smallholders and vulnerable people live in districts that will need special attention to improve food security.”

Activating the Wheat Seed Value Chain

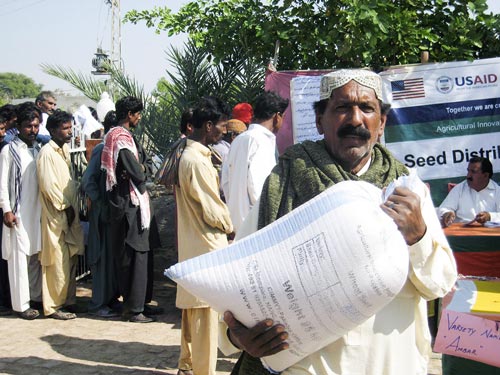

As a part of the Agricultural Innovation Program (AIP) for Pakistan, a project funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID), CIMMYT is working with the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC), BARI in Punjab, seed companies and farmers to close gaps in the wheat seed value chain for rain-fed Punjab.

Workshop participants cited the need for better communication and coordination of research and extension agencies with commercial input suppliers sector and, especially, better marketing of new wheat varieties to farmers. “If stakeholders don’t integrate and coordinate, small-scale farmers will remain deprived of modern technologies and innovations, such as wheat varieties that resist new and virulent disease strains,” said Joshi.

“If stakeholders don’t integrate and coordinate, small-scale farmers will remain deprived of modern technologies and innovations, such as wheat varieties that resist new and virulent disease strains”

– Krishna Dev Joshi

CIMMYT Wheat Improvement Specialist

Farmers recommended establishing village committees to choose and access seed of new varieties and help foster truth in labeling. They particularly called for strict punishment for those selling fake seed.

For their part, seed companies said the lack of reliable irrigation or storage facilities hinders seed production in Pothwar. “Because of this, seed must be transported over long distances, raising costs, which in turn discourages buyers and cuts profits,” said one company representative.

The workshop forged an agreement to allow private seed companies to produce pre-basic and basic seed, supervised by concerned breeders and with support from Federal Seed Certification and Registration Department, to speed the marketing of new varieties. One result was that Robert Cotton Association has received pre-basic and basic seeds of two wheat varieties, Chakwal50 and Dharabi11, originally developed and released by BARI, which will provide technical backstopping.

Other action points agreed on at the workshop included the following:

- On-farm trials and demonstrations that allow farmers to learn about and choose from new, high-yielding wheat varieties. To address this, AIP-wheat has already launched participatory varietal selection trials in which farmers and researchers jointly evaluate 14 new, high-yielding, disease resistant wheat varieties of diverse genetic backgrounds on the farms of 65 smallholders across Pothwar. In addition, to help farmers assess and improve crop management practices, the project is conducting 20 on-farm, participatory experiments on fertilizer use and 107 trials on pre-soaking seed, a practice that improves germination and crop establishment.

- Community-based seed production linked with private companies and supported by proper equipment and training in quality seed production. Achievements to date include seed of 9 new varieties being multiplied directly with 52 Pothwar farmers on more than 42 hectares.

Group. Photo: CIMMYT

Nutrition, health and food security

Nutrition, health and food security