In 2016, the emergence of wheat blast, a devastating seed- and wind-borne pathogen, threatened an already precarious food security situation in Bangladesh and South Asia.

In a bid to limit the disease’s impact in the region, the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI) collaborated with the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and researchers from nearly a dozen institutions worldwide to quickly develop a long-term, sustainable solution.

The result is BARI Gom 33, a new blast-resistant, high-yielding, zinc-fortified wheat variety, which Bangladesh’s national seed board approved for dissemination in 2017. In the 2017-18 season, the Bangladesh Wheat Research Council provided seed for multiplication and the country’s Department of Agricultural Extension established on-farm demonstrations in blast prone districts.

However, the process of providing improved seed for all farmers can be a long one. In a normal release scenario, it can take up to five years for a new wheat variety to reach those who need it, as nucleus and breeder seeds are produced, multiplied and certified before being disseminated by extension agencies. Given the severity of the threat to farmer productivity and the economic and nutritional benefits of the seed, scientists at CIMMYT argue that additional funding should be secured to expedite this process.

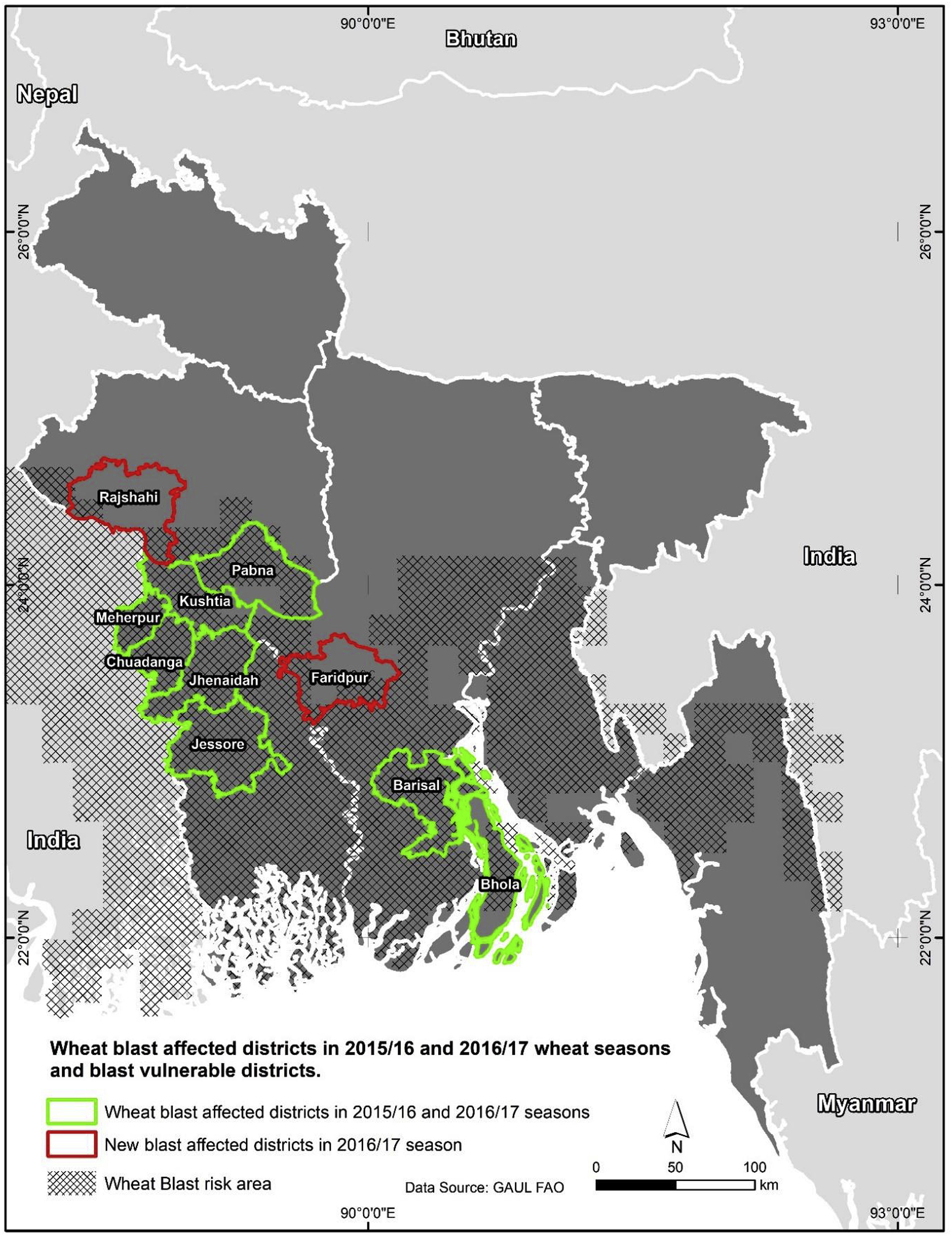

According a new study on the economic benefits of BARI Gom 33, 58 percent of Bangladesh’s wheat growing areas are vulnerable to wheat blast. The rapid dissemination of seed can help resource-poor farmers better cope with emerging threats and changing agro-climatic conditions, and would play a significant role in combatting malnutrition through its increased zinc content. It could also have a positive effect on neighboring countries such as India, which is alarmingly vulnerable to wheat blast.

“Our simulation exercise shows that the benefits of disseminating BARI Gom 33 far exceed the seed multiplication and dissemination costs, which are estimated at around $800 per hectare,” explains Khondoker Mottaleb, CIMMYT socioeconomist and lead author of the study. Even in areas unaffected by wheat blast, scaling out BARI Gom 33 could generate a net gain of $8 million for farmers due to its 5 percent higher average yield than other available varieties. These benefits would nearly double in the case of an outbreak in blast-affected or blast-vulnerable districts.

Based on these findings, the authors urge international development organizations and donor agencies to continue their support for BARI Gom 33, particularly for government efforts to promote the blast-resistant variety. The minimum seed requirement to begin the adoption and diffusion process in the 2019-20 wheat season will be 160 metric tons, which will require an initial investment of nearly $1 million for seed multiplication.

Read more study results and recommendations:

“Economic Benefits of Blast-Resistant Biofortified Wheat in Bangladesh: The Case of BARI Gom 33” in Crop Protection, Volume 123, September 2019, Pages 45-58.

This study was supported by the CGIAR Research Program on wheat agri-food systems (CRP WHEAT), the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (CRP-A4NH), and the HarvestPlus challenge program (partly funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation).

Nutrition, health and food security

Nutrition, health and food security