Support for smallholder farmers to trial and select sustainable practices suited to their varying conditions is essential to build resilient farms needed to feed Africa’s soaring population, said economist Paswel Marenya at the Second African Congress on Conservation Agriculture in Johannesburg this October.

Farmers face different agroecological, socioeconomic and institutional environments across Africa. The mounting challenges brought by climate change also vary from place to place. Family farmers are born innovators, with government and industry support they can develop a resilient farming system that works for them, said the researcher from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

One of the emerging paradigms of sustainable agriculture resilient to climatic changes is conservation agriculture — defined by minimal soil disturbance, crop residue retention and diversification through crop rotation. Although not a one-size-fits-all approach, it is a promising framework to be applied and adapted to meet farmers’ unique contexts, he said.

“Conservation agriculture’s potential to conserve soils, improve yields and limit environmental impacts makes it one of the elements that should be given prominence in efforts to secure sustainable and resilient farming in Africa,” he told audiences at the conference dedicated to discuss conservation agriculture systems as the sustainable basis for regional food security.

Along with eleven other researchers, Marenya presented evidence gathered over eight years researching the development of locally-adapted conservation agriculture-based practices as part of the Sustainable Intensification of Maize and Legume Systems for Food Security in Eastern and Southern Africa (SIMLESA).

“Research shows that with a network of appropriate support, farmers can access the tools and knowledge to experiment, learn, adapt and adopt these important principles of conservation agriculture,” he said.

“Their farming can thus evolve to practices that have low environmental impacts, diversify their cropping including intercropping maize with legumes, and test affordable machinery for efficient, timely and labor-saving operations. In the end, each farmer and farming community have the ability to tailor a conservation agriculture-based system based on what works best given their unique socioeconomic settings,” said Marenya.

Trialing sustainable practices leads to adoption

Through the project over 235,000 farming households in the region have trialed sustainable practices reporting positive results of improved soil fertility, reduced labor costs, and increased food production and maize yields despite erratic weather, said collaborating investigator Custudio George from the Mozambique Institute of Agricultural Research.

“The majority of these farmers have gone on to adopt their preferred practices throughout their whole farm and now actively promote conservation agriculture to other farmers,” he added

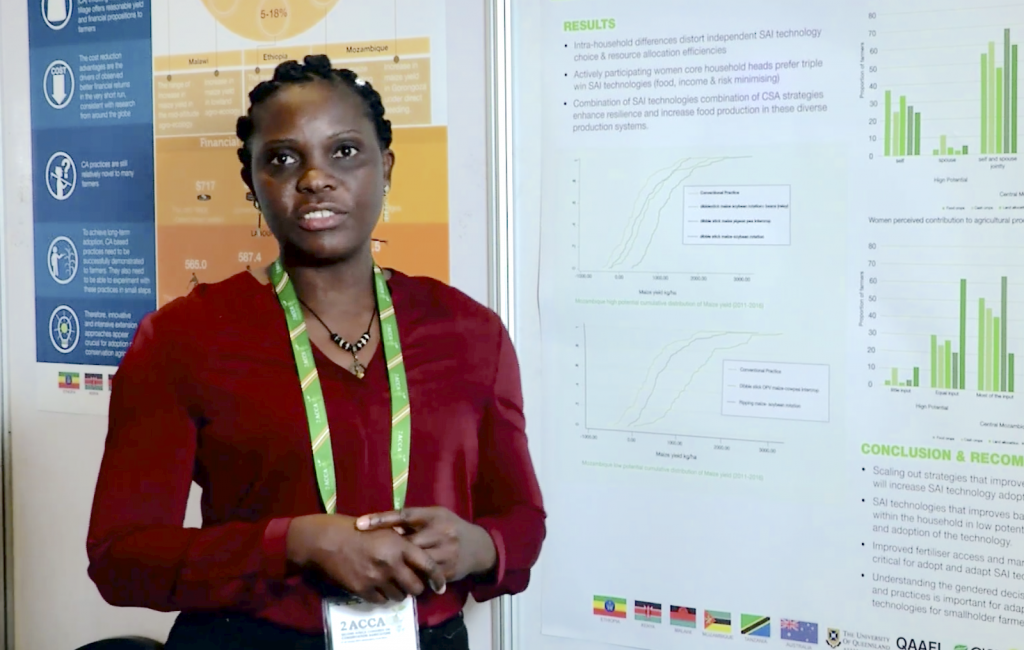

Women undertake the majority of agricultural activities in sub-Saharan Africa. When they are empowered to try sustainable practices they overwhelmingly adopt those technologies identifying them as an economically viable way to overcome challenges and increase household food security, said Maria da Luz Quinhentos, who is an agronomist with the Mozambique Institute of Agricultural Research.

Forming networks to support farmer resilience

The research project took a multidisciplinary approach bringing together sociologists, economists, agronomists and breeders to study how maize-legume conservation agriculture-based farming can best benefit farmers in seven countries; including Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Uganda.

In this vein, the project sought to connect farmers with multi-sector actors across the maize-legume value chain through Innovation platforms. Innovation Platforms, facilitated by SIMLESA, are multi-stakeholder forums connecting farmer groups, agribusiness, government extension, policy makers and researchers with the common goal to increase farm-level food security, productivity and incomes through the promotion of maize-legume intercropping systems.

“Having a network of stakeholders allows farmers to test and adopt conservation agriculture-based techniques without the risk they would have if they tried and failed alone,” said Michael Misiko who studies farmer adoption as part of SIMLESA.

“Farmers form groups to work with governments to gain access to improved seed, learn new farming practices and connect with local agribusinesses to develop markets for their produce,”

“When new problems arise stakeholders in local and regional innovation platforms can diagnose barriers and together identify mutual solutions,” he said.

Researchers and governments learn from innovation platforms and can use results to recommend productive climate-smart practices to other farmers in similar conditions, Misiko added.

Climate-smart agriculture key to achieve Malabo Declaration

The results from SIMLESA provide African governments with evidence to develop policies that achieve the Malabo Declaration to implement resilient farming systems to enhance food security in the face of a growing climate risks, said Marenya.

Hotter temperatures, increased dry spells and erratic rainfall are major concerns to farmers, who produce the majority of the region’s food almost entirely on rain-fed farms without irrigation.

If these smallholders are to keep up with food demand of a population set to almost double by 2050 while overcoming challenges they need productive and climate-resilient cropping systems.

CIMMYT research identifies that the defining principles of conservation agriculture are critical but alone are not enough to shield farmers from the impacts of climate change. Complementary improvements in economic policies, markets and institutions — including multi-sectoral linkages between smallholder agriculture and the broader economy — are required to make climate-resilient farming systems more functional for smallholder farmers in the short and long term, said Marenya.

Nutrition, health and food security

Nutrition, health and food security